—Written in April 2020.

It’s just a flu.

Since January, I have been consuming too much news regarding the Covid-19 situation in Wuhan and losing sleep worrying about my family in China. As a senior who lives on campus at a liberal arts college in Los Angeles, I have always been surrounded by caring friends and professors. Nevertheless, I felt very lonely at the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis. Because very few people, probably only Chinese students who have families in China, shared the fears, helplessness and anxiety that I was feeling at that time. For my American peers, coronavirus was just a novel term, a new SARS virus, or something that’s less serious than a common flu. It was so trivial and distant that, when I went on a retreat for my department, somebody put in “coronavirus” and “Wuhan” as terms for our charades game. The similarity that the virus’ name bears with the Corona beer also turned it into a great meme material that became viral in various college meme groups. To a lot of Americans, “coronavirus” was just a buzzword; it was not lives lost, jobs lost or families shattered. Or at least not yet. However, I didn't really know how to voice my frustration to my friends or professors, because I have long come to terms with the fact that, as a foreigner, I lived in a white-majority country. I never counted on people to understand or care about the issues that I was dealing with that originated from back home. Especially with Covid-19, it was hard for me to gain sympathy as a victim of a disease that was arguably caused by my own country.

We are not a disease

In February, as the coronavirus started to spread across the world, so was racism against Chinese and Asian communities at large: one Vietnamese woman was subject to humiliating racist comments from other passengers on a bus in Paris, a Singaporean student was beaten up by some random passersby on Oxford street in London, while Asian Uber drivers in the US are begging riders not to cancel rides just because they have Asian sounding names... When I called a Chinese friend who lives in Paris to check on her, she jokingly told me that life had never been this great: she no longer struggled to find a seat on the metro during rush hour, because as soon as she stepped in, everyone would cover their mouth and nose and flee away. Having lived in Europe and the US, I too have encountered racist incidents. I often choose to dismiss their attacks as ignorant and want to believe that they are just a minority. Nevertheless, I had never experienced this much fear of being East Asian— a fear of being reduced to a disease which gives people the license to hurt me. I started looking for tickets to go home to China for spring break. The fact that there was a travel ban between the US and China meant that I couldn’t really go home. However, the thought of being back in a place where I am not just a race but a human being—a place of solidarity where everyone is going through the same thing— brought me a sense of solace and comfort.

I thought that living in a diverse and progressive city like Los Angeles would shield me from racist attacks, but sadly I was wrong. The weekend before I left the US, when things were still normal and the world was not ending, I went to visit an art museum in downtown LA with another Asian friend. I was holding the elevator for a group of people, and after they entered, one guy fake coughed and said: “I feel like I’m going to get coronavirus.” I was completely caught off guard and tried to calm myself down by thinking that maybe I had misheard. But his friends were shocked and told him that it was not ok to say such things. The man thought that he was being funny, but still felt pressured by his friends to explain himself: “Oh I just thought that my throat has been dry and itchy for the past few days.” His friends were visibly mortified and tried to make up by saying: “then you should drink more water. And you shouldn’t say stuff like that.” My mind went blank and I completely lost my words. My college education has taught me how to fight systemic racism, but never taught me how to defend myself in front of a racist, especially when the person also happens to be of color. After we got out of the elevator, I told my friend: “I need to get out of this place. I can’t do this anymore.”

How to travel illegally

A few days later, on March 11th, my school announced that it would move the rest of the semester online and that the campus would shut down. I immediately bought a ticket home, even though I could stay on campus as an international student. My mom didn’t want me to come home, because being in an enclosed space with potential virus carriers for over 20 hours is too risky. There were a lot of other things to consider as well. For example, I would have to take my classes at 4 am China time. Due to the travel ban, I might not be able to make it back to the US anytime soon. In addition, I was still waiting for my post-grad work permit to be processed. However, since I had already been so emotionally exhausted, all I could think about was going home. Plus, my city, Chengdu, had lifted a lot of lockdown measures at the beginning of March. I thought that the situation could only get better if I chose to go home, while the situation in the US would worsen before it gets better.

Originally, I booked a flight for a week later, giving myself time to pack and celebrate the end of college with friends. Nevertheless, after the first Covid-19 death in Los Angeles county occurred in a hospital 20min away from my school, I completely freaked out and changed my flight to 3 days later. As countries were starting to impose entry or transit restrictions, and quarantine policy for returnees to China was becoming stricter, I was basically racing against the clock to make it home before having to undergo collective quarantine imposed by the Chinese government.

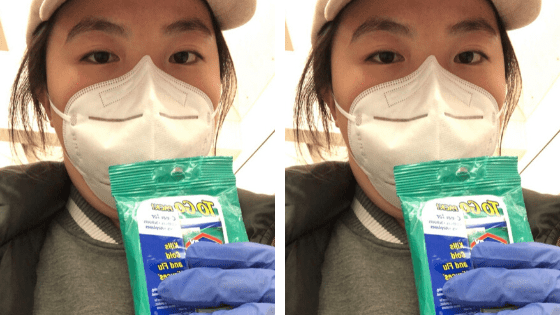

On March 15th, I packed up 3.75 years of my life in the US, hugged my friends goodbye without knowing when I would see them again, and embarked on a long and arduous journey home. A day before my flight, Taiwan, where I was transferring, imposed a ban on Chinese passport holders from transiting through the airport. I had a mental breakdown after receiving the news. But after hearing stories about some people making it through while some others didn’t, I decided to still go to the airport and try my luck. At the check-in counter, the airline told me that, although it was technically illegal to let me go to Taipei, they would still let me board, since the airline had already sold me the ticket. The only thing was that I absolutely must not show my passport to anyone at the airport who doesn’t work for the airline, because otherwise they would report me to the Taiwanese authorities.

After 20 hours of “illegal” traveling, wiping down everything that I touched and breathing through a suffocating mask, I finally made it to Chengdu, China. We were told to wait in the aircraft on the tarmac, and they disembarked ten people at a time and checked their temperature. I glimpsed at a paper that the flight attendant was holding and saw a list of our names ranked based on the risks of the countries we flew from. Although at that time, the US only had less than four thousand cases, it was already listed as a high-risk country for some reasons. After almost one hour of waiting, I was called off the plane. We were then shipped to another terminal hall before being sent to take a swab test. As the Covid-19 situation outside of China continued to deteriorate, and schools across the world were shutting down, many Chinese expatriates found it safer to go home rather than staying still. As a result, the airport was overloaded with a sharp increase in people returning from abroad. Although I had filled out the health declaration on board, every passenger still had to sit down with a staff member from the public health bureau to verify our information. Talking to me through the plastic face shield of her full-body PPE gear, the lady verifying my information told me that she had been working an 8 hour shift everyday at the airport since late January. It was a breezy spring day in Chengdu with a temperature of around 20 degrees Celsius, yet I could barely see her eyes because the face shield was blurred by droplets of sweat.

Four hours after I landed, I finally left the airport and was sent off to a hotel nearby to wait for the swab test result, which usually takes a day to process. The majority of travelers on the plane were Chinese students of the same age as me coming from the US and Europe. So, on the shuttle to the hotel, we were exchanging horror stories of how some of us almost didn’t make the connection, struggled to secure masks for the flight, or found the plane ticket the night before for a ridiculous price. The conversation was light-hearted and filled with laughter, as we all safely made it home despite the horror stories. We also made fun of one kid who flew from Barcelona wearing a gas mask. Although I was still wearing a suffocating mask, I felt like I could finally breathe after three months of anxiety, one week of panic and twenty hours of hyperalertness.

Life as a biohazard

I had always known that the Chinese government is gigantic and complex, but never fully understood its size or complexity until now. From touching down on the ground to checking into my hotel room, I was passed along by people from different bureaus or branches of the government: the bureau of public health, the ministry of exit and entry (border control/customs), the police, and officials from the city and district governments. Even at the quarantine hotel, I was monitored 24/7: somebody from the public health bureau would come take my temperature in the early morning and late afternoon, and somebody from the hotel would deliver my three meals, and somebody else from the district government surveilled the floor all day long. As a precautionary measure, everyone was fully dressed in PPE, and even when they delivered food, they would put it on the floor and knock on my door to avoid direct contact with me. I got scolded once by the government official, because I opened the door to pick up my food without putting on a facemask. It was quite a surreal feeling being treated as a biohazard.

I didn’t unpack because I thought that I would be sent home for self-quarantine when my test result comes back negative. Nevertheless, two days passed and there was no news at all. The third morning, I was informed that I was being transferred to a hotel in my district, because Chengdu had just abandoned the policy of self-quarantine, and it is now collectively quarantining anyone coming back from high-risk countries. Additionally, one person on my flight from Taipei to Chengdu had been diagnosed with Covid-19, which made me a high risk person. As hundreds of thousands of Chinese like me were flocking back to the country, we imposed an unprecedented threat of a second outbreak. As a result, various local governments, including Chengdu, stepped up control measures on returnees, because they couldn’t risk jeopardizing two months of sacrifice made by millions of people to contain the virus.

That night, I was picked up by the district government along with around ten other people, and we were en route to another hotel for eleven more days of quarantine. Our bus kept circling the district because two of the designated hotels for quarantinees had just been filled up. I can hear the government official in charge frantically calling hotels and booking websites trying to find a place to accommodate us. People were getting agitated and started complaining. Eventually, he stood up and explained to us that, because the policy of collective quarantine had just been implemented, all the district governments were scrambling to find hotels that were willing to undertake such a risky task of hosting people with high risk of infection. He went on to tell us that he had been working since 6 am (it was 9pm at that time) and had barely had the time to eat or drink. He had been working nonstop since late January, and just as he thought that he could finally have a breather in March as domestic cases have fallen significantly, he got called back to work due to people like us returning from abroad. I guess because he was equally frustrated by the situation, he continued the rambling stream and told us that he hadn’t seen his wife for 3 months. She is a nurse and was sent to Wuhan to help local hospitals. Although she has returned from Wuhan, she is now under quarantine in a resort, and she would be sent to Italy afterwards to assist hospitals there. He also had to send his son to stay with his parents, because he couldn’t take care of his son. After his speech, the entire bus went silent and people stopped complaining.

11 days away from home

So there I was eventually, in a new hotel room 15min away from home, but 11 days away from actually arriving home. I had to cover the cost for the rest of my quarantine time, which meant $30 per day including 3 meals. I really had nothing to complain about, because I safely made it home (sort of) against all odds. However, a lot of my friends didn’t get as lucky: the Chinese government announced that, beginning April, they would cut around 90% of international flights coming into China to reduce the strain on the healthcare system. This measure in a way burned the bridge to go home for many Chinese students who are still stranded abroad. With foreign airlines grounding fleets and only Chinese airlines still operating in an extremely limited capacity, ticket prices consequently skyrocketed. When I went home in mid March, I paid around $700 for my flight, which is already pretty expensive compared to normal times. After the measure was implemented, tickets to China from Europe or the US soared to $2,000 and beyond, and they are often really hard to come by.

A few days into my quarantine, my mom texted me and asked me to delete my social media post telling people that I had returned from abroad. She said that her friends had stopped asking her to meet up as soon as they learned that I was back in Chengdu (but not even home). There was also a growing outrage from the Chinese public against students who had returned from abroad, because apparently we “traveled thousands of miles to poison the country (千里投毒).”

After spending two months in the US fearing that people would see me as a disease, I’ve actually become one in my own country. In a way, I do understand this anger against us. Because we are rushing back home, all the government employees who have been working nonstop since January have to continue doing so. At the same time, it saddens me to see that, when other countries were airlifting their citizens out of Wuhan when the virus first broke out, my country is shutting its own citizens out when the crisis abroad is at its worst. If we can’t go home, then where can we go to be at our most vulnerable?