A Conversation with M’barek Bouhchichi on Art, Race, and Deconstruction

M’barek is an artist born in Akka, Morocco. One of his most recent works focuses on the history of black Amazighs in southern Morocco. He highlights many of the community’s practices in order to bring forward the established divisions of space and labour in Morocco.

I first encountered M’barek at the Kulte Gallery in July 2019 in Rabat at a roundtable themed on races and identities in Morocco which he chaired along with the Historian Rita Aouad. At the roundtable, M’barek repeatedly mentioned occurrences in which Black Moroccans continue to be invisible in public spaces, notably from television, — unless enacting specific roles that reinforce racist connotations and misrepresentations— and in the political arena. This interview is an extension of a conversation that must crucially be amplified. I asked M’barek about his artwork, inspirations, and the ways in which he bridges the seen, the unheard, and the silenced.

Amina: I truly enjoyed listening to you last week at Kulte. You know, as soon as I got home after the roundtable, I spent a lot of time thinking of what it means to be denied one’s identity. To be outcasted. I thought about my own experience at my former university, a space in which being African was synonymous with being black, and we live in a society in which being Moroccan, and North African in general, is often not synonymous with blackness. I have prepared a couple of questions for you, but first, I just want to thank you for making time.

M'barek: With pleasure, this is part of my work which primarily revolves around three things: I am either working on collaborations through which I am able to put into question the status of the artist in the context of Morocco, or I am part of a working group, or I simply extract myself from the group. However, I am positioned in a group that was defined by the “other.” A reason why I believe it is essential to communicate about these fabrications and constructs and to sublimate them through art and also through speaking up. It is important.

Amina: I am very curious about who you are, and I have spent a great deal of time reading many articles that have been written about you. But it would be wonderful to hear about who you are in your own words.

M'barek: Well, I don’t know what to say, I am M'barek. I am a man who was born in a context that isn’t known amongst Moroccans, or rather, a context that hasn’t been given a name by Moroccans. They often refer to this place as the desert الصحراء. This desert is related to emptiness الخلاء. This emptiness is an unknown territory that many Moroccans can’t identify, and prefer not to give a name to.

We can think of it like representation in Western paintings. Sometimes you come across a painted portrait of a duke with a well written name tag next to it carrying the name of that duke. However, right next to it, you’ll find the portrait of a black man, and they will simply refer to him as “un nègre” he doesn’t have a name...you see what I mean. The desert is there but it is not there at the same time. It is a place characterised with distance, a constructed distance, where often the Moroccan individual doesn’t identify himself or herself to it.

I was born in a geographic and historical margin. I was born in Akka. A place that has had many influences on Moroccan dynasties such the Saadian dynasty, the Almoravids, and the Almohads. It was the hub for trans-saharan trade.

I am from there and I am an immigrant. I feel that I am an immigrant because my parents left there when I was about three months old. I became an immigrant when we found ourselves in a new context, away from the place I was born. I feel that I have gone through an internal immigration, still within a national context. After that, voila, I am who I am today. I can’t define myself as an artist or an activist. I am someone who is here to observe and transcend things, and to transform forms and speak about matters. It has been about twenty years that I have been teaching art which is an interesting endeavour and also a primordial one in regards to the process of construction in Morocco. It’s an imperative logic of construction, which sometimes distances me from my logic as an artist, and feeds into it. This somewhat means that I do not submerge myself in the fabric of social conflicts, or rather, social hierarchies, however I find myself speaking about art in a language that is different from the one that forged my imagination.

I find myself in spaces with ambiances similar to laboratories. This has led me to ask myself many questions over the past years on what I was taught at school. Art, for instance, allows me to express my sentiments and opinions on many situations because at school, the western world was a constant reference point through which the hierarchy of art was established. And I felt weak and admirative in relation to it. However, I could not help but feel that I was turning my back to an essence I was born into and grew up within. It is a place where there was an alphabet and a language that had been defined by the Westernization of folklore and artisanal work. The artwork that surrounded me was articulated through a language that created a distance and a sort of uprootedness between its various elements and myself. Today, I continue to formulate questions and observe.

Amina: My next question is about your encounter with art. How did that come about? How did you choose this path? And also perhaps how did the context in which you grew up in continue to influence your artwork? I know that this does seem like a rhetorical question, we often say that what we go through remains at the centre of our creativity. I am curious to hear it in your own words— about this voyage that you have been through, when did everything start?

M’barek: Well, I started like everyone else. I started in my own context. I am a painter, and it is painting that allowed me to position myself, to feed myself, both in material and intellectual terms. I was the subject of my own work. It was a quiet expression without discourse. At the same time I felt things, thoughts and imagined.

I received a lot of violent punches that led me to question where I came from. There were instances where I happened to be invisible. I was assaulted, sometimes to the extent to which I was deprived of my appartenance. It’s an accumulation of many events throughout my childhood and my early teenage years. But it was also a matter of chance, le hasard des choses.

I had to take pause. A long retreat, a moment of rupture of almost three years. I took refuge in my own home, I boycotted all exhibitions, I was disgusted by everything. That is when I encountered the work that I produce today.

I first started with understanding and submerging into this third identity, the African-American identity. I spent a lot of time reading the literary work that have come out of the African-American movement because it was the most accessible literature on blackness, and also because it openly expressed the black experience: what it means to navigate the world as a black person today. And this African-American experience, although located within the context of the United States, had become exported to the rest of the world, speaking on behalf many other experiences. I was fascinated by it. I researched a lot. I read a lot. And I questioned the possibilities of creating something as well. It also led me to question history. I was reading on the liberation of slaves in the United States, I was reading on Abraham Lincoln, and I thought to myself this is a bit of bullshit. I considered it as an interesting point to disturb history and to break it apart. Because the essence of a human being, I believe, is to deconstruct.

I began deconstructing the myth. I realised a first artwork that I called “L’invention de la machine libérale homme noire” (the invention of the liberal black human machine). Because I understood that the liberation of slaves was about flipping things around, it was serving the purpose of an economic reality.

Now, because I believe profoundly in encounters and in the concept of companionship in life, I was contacted by Omar Berrada, an individual who happened to play an important role in the liberation of my voice on this topic.

Today, I am in a phase in which doubt sometimes takes over me. I begin oscillating between believing and not believing. When presenting my projects in the country, I can hear the echo that is projected towards me from Moroccan audiences, which make me dive into a frustrating duality. I am often told “oh, but this doesn’t exist” “we are all Moroccans, there is no such thing as a Black Moroccan.”

Recently, I was in Tunisia and I was doing research and I wanted to see the correlation that can be created with a context like ours. I found many similarities. There is segregation: “Jettate el Wesfan” in Djerba or “Ein el wesfan” The verbal violence against Black Tunisians I would say is even worse than Morocco. There are individuals who still carry the last names of the families to whom their great grandparents belonged to as slaves. Today I truly wish to disturb this geography, question this inequality through art in a much larger context. I would love to go to Mauritania, Egypt, Libya and observe what is happening in this region that we call North Africa.

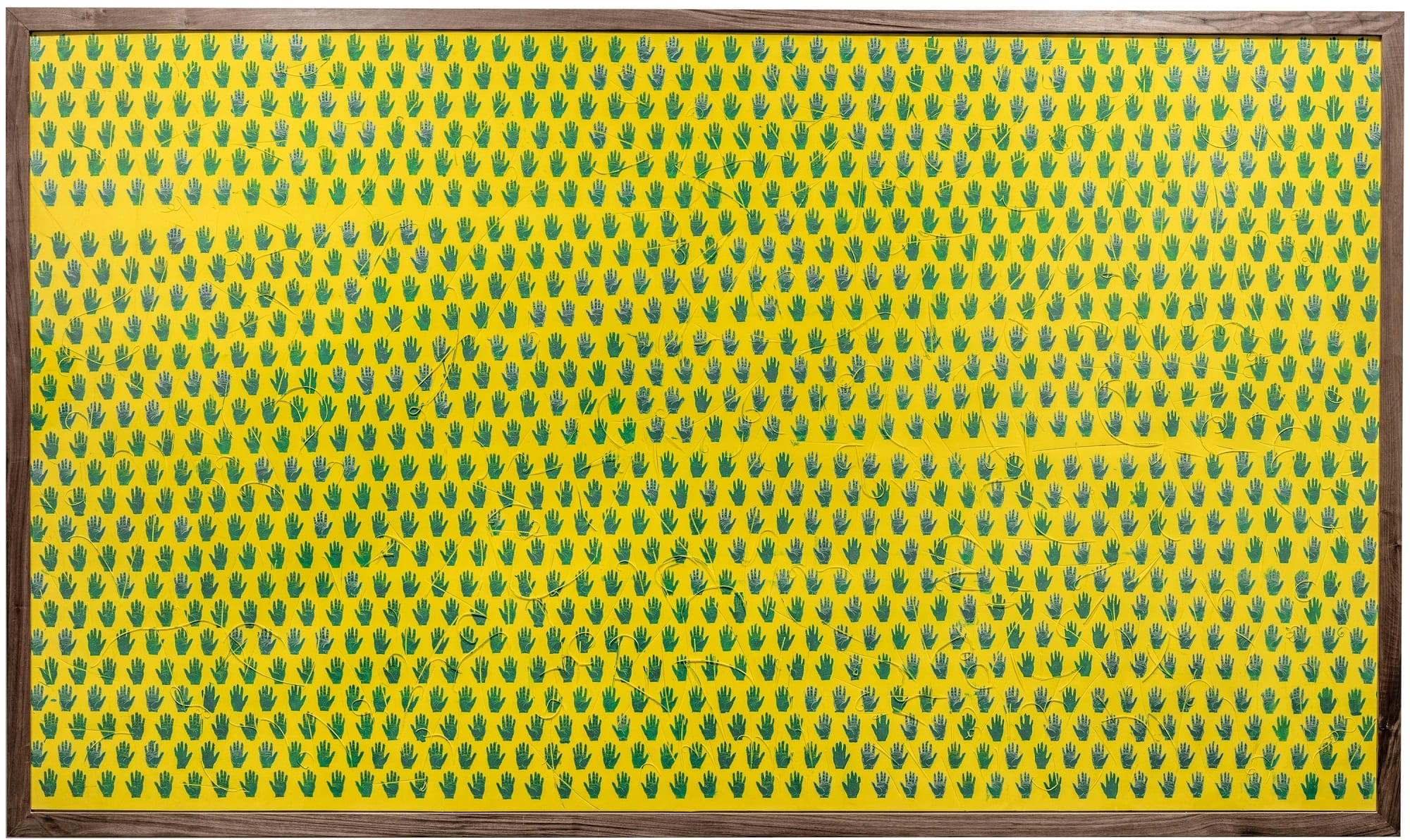

Amina: I have noticed that you use a lot of green in your artwork, was it just for one specific exhibition, or does green have a specific significance to you?

M'barek: My beginning in painting relied on a vast majority of natural pigments. It was through my grandmother, who continues to mark my existence, that I learnt techniques which school would have never taught me. She provided me with natural pigments. I began questioning this combination of color made of ocher, earth colors and attenuated hues. But the phase of green happened at some point. I remember it. It was in relation with learning how to process thematiques of space and spatiality as entities constructed through the gaze, that reflect us, yet disturb us with their material and psychological elements.

Nowadays I have a tendency to use natural colors in my work. I don’t want my artwork to exist in a landscape of make-up. I am constantly seeking an aesthetic that speaks to the color of ceramic, to the color of the earth, the soil, colors of metal and weaving. I try to engage with other forms of aesthetics that have not had any grand industrial interventions.

Amina: I am curious about the book you have recently contributed to“The Africans”. How can the book raise awareness in Morocco and North Africa about the segregation and inequality that dark skinned individuals encounter?

M’barek: First of all, I truly want to stress that the “Africans” was published well before the re-integration of Morocco to the African Union, before all political discourses, which happened in 2017. The book came out in February 2016. The Africans was about assuming our Africanness and articulating that we are Africans. In the book there isn’t only me and Omar Berrada, there is Ali Safi, Emmanuel Iduma and Stefania Pandolfo. It was about rethinking another Africa— an Africa that is more human to a certain extent.

I believe that the conjecture of that moment was interesting. It was a moment of debate on the trans-saharan mutation. Morocco saw itself becoming the safe guarder of the European border, working tirelessly to ensure that the south of the Mediterranean remains white. Morocco also saw itself transitioned from being a crossing bridge for migrants to a final destination.

Following that, we started witnessing a level of schizophrenia that reached a significant peak. On social media and in the streets violence against sub-Saharan individuals was clearly committed. People wouldn’t rent their homes to “Africans,” and these were the messages that one could see written at the front door of several rental homes. It was funny, it was a moment when Moroccans suddenly had forgotten that they were Africans. It was a moment when things had to be spoken.

This Moroccan is confused on whether he is Arab, Amazigh, African or European. He is fascinated with whiteness: the whiteness of ideas and whiteness of skin, whiteness in terms of hierarchy and supremacy over others, and whiteness in terms of race, an attempt of positioning his/herself. It was a moment for us to say that we need to experience Africa historically. There was a need to understand what our role has been, in the building of this continent, what our current role is, and the shape that it will take in the future. It was also to speak of invisibility, to announce that Africanness goes beyond skin complexion, it is something else to define and redefine but — together.

Amina: In regards to the processes through which Morocco has been whitewashed and un-africanized, can you elaborate about specific examples on how that has been done?

Mbarek: Recently I have seen examples that have reassured my belief on how the tradition of western art has misrepresented us. When a Mauritanian, a Moros was painted, he was represented as black. You can find this in the paintings of Piero della Francesca. You can find it in the Corsican flag today, the black decapitated head. The Sultan Moulay Ismail for instance was a black king. Youssef Ibn Tashfine was black. Morocco is Black, and I want to say that.

The issue that we encounter is that any black found in Morocco is told to have come from Sub-Saharan Africa. And this is where they are wrong. I am from here. I am here. And there is something that needs to be fixed, perhaps it is the other who is an immigrant. Why would you tell me that I am an immigrant, and that I come from elsewhere? This tendency of whitening for me is a project of creating the “south of the Mediterranean” because the Mediterranean needs to remain white. I consider that the first Greek statues were all painted in shades of gold, however, today they use white marble, daltile. This has led to the question of race in the west. They wanted to create an island in Africa, called "North-Africa" that is desired as white, to ensure that imaginaries perceive this Mediterranean to belong to Europe —this little continent that continues to dictate the history of other continents.

This question of whitening is also visible in the daily life of the Moroccan. We can think of this competition of wanting to be married with a white girl. The lighter and whiter her skin is, the more beautiful she is, by default.

Amina: This reminds of Franz Fanon’s Black Skins White Masks, and how marrying a white person is an attempt to enter a white realm that can offer one more status in the community or society s/he is part of.

M’barek: Exactly, I am currently doing some writings for a project I am working on and there is a paragraph that I begin with: being white is a status. And how there is this fascination with wanting to make everything white. We can even see how this translates in radical ways. Let’s think of ads on Moroccan television, they often capture a family, that is white and that has caucasian features. Creating an imagined Morocco, in which whiteness is at the heart of the social imaginary.

Amina: From your talk at Kulte, I remember that you stressed tremendously on this notion of deconstruction. How can a Moroccan citizen begin his/her journey with deconstructing this notion of race?

M’barek: The essence of a human being on earth is deconstructing and it is not construction. I love words that begin with “re” like re-define, re-construct but through deconstructing. I’ll give an example that is a bit out of context. My first voyage to Italy was driven by a fascination to observe the cohabitation in Rome between the modern buildings and the historical ruins, everywhere, how people can dig up their gardens and be able to find objects from another era. However, these days when I get to think about this, I sense that it is dangerous. It becomes an act that can block the journey of a human being. I began thinking about the kind of relationship one can carry or develop with history. History weighs heavily.

Sometimes I think of Iceland, a country that is still moving geographically and geologically speaking. There are many erupting volcanoes, and the earth is constantly moving and so on. Would it be possible to think about heritage, and what one can transmit? I am speaking of the materiality of the physical realms.

In Morocco, I think it is important to begin with deconstructing the gaze, stereotypes, language, habits, and les choses, things that deeply limit us from the simple act of seeing clearly what is in front of us.

We can start by deconstructing this prevalent obsession with blood kin ties. I have the impression that we (as Moroccans) are still living within a construction site that attempts to make blood الدمand the tribe La tribue as the sole legitimate way of being worthy of living. You have families who would not allow their kin members to marry foreigners, and worse to marry a black person. However, at the same time you can find contradictions within that same family. Those individuals who claim to want to sustain the purity of their family blood have had black grandfathers and grandmothers, or have had people in their tribe who are black. We truly need this form of deconstruction today.

I practice deconstruction through many layers as I have mentioned. I was once asked on what I thought about an exhibition I had done. For me, the exhibition was nurtured through the embodiment of the collaborative context in which it was born.

I have a tendency to collect things. I love collecting things. I love discovering, and digging things up, flipping the earth to let it express, speak, and talk in alternative ways of being that individuals weren’t able to articulate. I like to bring onboard historical elements and human experiences, both, with what individuals can make with their hands, and with the inherited materialities. These inherited materialities that sort of form a danger, because we have been constructing images as opposed to creating them throughout our history in Morocco.

We produces images that have been subject to a western gaze, whether that is a painting, a photograph, a project, or a movie. However, these constructed images that are reproduced in Morocco, often, lose their primary function. They become static, yet oscillate between being decorative and fascinating.

I depart from the precarity of things and imperfections to create traces and to question the possibility of deconstructing. I don’t see this deconstruction as a violent act, or a vertical one. I believe in a collective horizontal deconstruction that can happen through the reactivation of various forms of mutual collaborations that we once used to have in our society, and have lost due to the colonial déchirure. I am thinking of the works of Twiza, the collaborative work in the fields, or within spaces of celebrations, and within villages that didn’t belong to anyone, but rather belonged to the entire tribe الجماعة. These elements of collectivity are important. I want to walk with people and deconstruct many things that remain suspended in the imaginary, blocking our minds and gaze. These fragments that do not allow us to think further.

Amina: If you had to recommend a book, a song, or a piece of artwork that can help individuals make a first step towards this journey of reconstruction?

M’barek: This is quite difficult. I will say it differently. There is a book that I love tremendously, that is alive and is still being written. It has a power in its writings, and also in the ways in which it survives and resists. It’s a book that exists in the Moroccan mountains and behind these mountains. It is the lived reality and experiences of those who live in the mountains. I can only ask you all to go and see it, participate, go witness a different reality that writes itself.

Amina: This reminds me of the villages near Chefchaouen which you referred to as invisible. They were inhabited by individuals whose addresses were based in other cities in the North, like Tangier and Tetouan. This realisation was truly profound for me. In what ways did this discovery inspire any of your recent works?

M’barek: In the project I am currently working on I am thinking of places of memory and remembrance. What is a space of memory? What are acts of remembrance? Can an act of remembrance be an act of mourning? Do localities of remembrance and memory seek their legitimacy from the political realm? Do they need to be situated within a date, a memorial, or is it an individual’s duty to reconcile with the localities of remembering? These are spaces that are still suspended in time and hold a silent violence. For instance, I had mentioned black communities that cannot be found on maps. They are invisible. They live with identity cards that carries an address of a cousin or a relative who lives in the city, and not the address of their village douar. They are not even registered in electoral lists; they do not vote. An extreme form of invisibility which no one speaks about.

I remember a village near Merzouga called Khamlia خملية, a place half eaten by sand. You can find a group of young men gathered in a house singing Gnawa for visitors that pass through. They receive a little bit of money from them. I found that quite powerful for an entire village to be sustained through such small incomes. I wish to be able to collaborate with some of these communities and with villages in the north someday.

Amina: Going back to your art, do you think that it finds a more appreciative audience outside of Morocco than in Morocco itself?

M’barek: For me this process of making art is similar to writing a bunch of letters and sending them to a maximum number possible. It doesn’t really interest me to know where these people are. I am not addressing a particular region per se. My work doesn’t have violence, well there is violence but it is expressed differently. It carries within it an aesthetic form that hides behind it another layer of violence which is linked to topics that are still taboo. Personally, the biggest and larger public that I would like to reach is the people with whom I work. The people I meet in the villages. These days, for instance, I was contacting an organisation of majorly black women in a village in the South of Morocco that are engaged in an extraordinary tradition of weaving. I actually brought a number of natural paint with me from my last trip to Tunisia, and I would really like to do something with these women. In a way it would be about creating a bond with a perishing artform, and a sort of correspondence between two audiences, two communities that are far from one another, and isolated from their surrounding as well.

Amina: Can you please tell me more about these communities that you work with?

M’barek: I have worked with potters in Tamagrout, and with craftsmen and artisans who work with metal in Amezrou, both in the region of Zagora. I worked with other artisans in Marrakech who originate from Kalaat Meggouna, and I am going to be working with a community of artisans from there soon. However, there are often some artwork projects that I can’t work on directly with local artisans per se. For example, I realised a project with a French artisan who lives in Morocco. And it was interesting for me to work with him on a topic such as land appropriation. It was in a way an attempt to question timeframes and contexts.

Amina: And when speaking of race, of your art and on Black Moroccans, do you consider yourself giving a voice to a minority? I am not sure if one can do a parallel comparison, but I have also been thinking about artwork produced about Afro-Iranians, and there is an emphasis on their experience as a minority.

M’barek: I actually don’t like the word “minority.” As I mentioned, I depart from this idea that Morocco is black, and whoever is racing to become white will never reach the Greek embodiment of whiteness.

When you look at the data, you’ll see that it mentions that Morocco’s black population is 10%. I like to be radical and reverse it. I see everyone as black. In my childhood, I didn’t use to distinguish, but as I grew older, and with school and encounters in the street, I learnt that I looked different. Let me tell you a joke, I am not sure if I mentioned it before. It’s actually not a joke, it’s a reality. It was during my first trip to Senegal. I got there, and I was surprised. I began looking right and left. And I saw myself. I didn’t feel that I was being looked as a different subject, a different body. It was the first time in my life that I felt that I belonged to a larger mass of people. It was the same sentiment that I had in the village where I was born. You had a few light skin families but the majority were black. It became peaceful inside me. I felt comfort.

There are other instances that revive in me this sentiment of belonging, when I encounter someone who looks like me. Often, I would be walking in the street, and I would spot another black person. We would exchange eye contact. It is a sort of sympathy that finds its way at that specific moment, because both of us carry a sentiment of being different, foreign غريب to the space. I suddenly feel that I am adopted and welcomed into the realm of an other who looks like me. I encountered this in a trip to a Tunisian village I took as part of a large group. The white people who were with me were, somehow denied to be part of the space, but I was asked to remain along with two other black Tunisians. At that moment, one of the locals looked at me and said “توا نقدو ندوو ” “now we can talk”. It is an expressive form of solidarity — one that reveals something. I don’t know what to call it, but it is there.

Amina: On this solidarity, I had an experience of a different taste just a few days ago as well as I was walking in my neighborhood. I exchanged a smile and made eye contact with a woman who was driving a fargo, a motorbike on three wheels. That exchange of smiles truly felt as if we were both complicit in supporting the audacity of her existence, a way to say “I support you, and I encourage your resistance.”

M’barek, thank you so much for your time and patience.

M’barek: With pleasure بالفرحات as they say. Welcom, mrahba, مرحبا.

Interviewed, transcribed and translated from French/Arabic by Amina Alaoui Soulimani