Foreword

Writing this piece took a long time – I had a whole lot of momentum when I started in early July, which I lost and regained a handful of times. It took a long time because it felt convoluted. Because I feel it slightly odd to be addressing anti-Blackness as a Brown woman (is it my place, really?) Because I’ve entered the sphere of social discourse relatively recently and am learning that I need to hold myself to a high standard. Because I want to be as informed as possible when I present information as facts, which is no easy task because a lot of what I’m saying lacks a tangible paper trail. In this piece, I’ve tried to juxtapose my own realizations about my exposure to anti-Blackness with accounts I’ve read and heard about. It’s another vulnerable think piece, with reflections on my own performative allyship and problematic behavior. My goal in writing this is in part to document my thought processes but also, hopefully, to acknowledge my shortcomings such that I may move past them. It still feels inaccurate and potentially incomplete and I will return to it as and when new insights inform my thinking. If your exposure to anti-Blackness differs from mine, please note that this in no way nullifies my experience or yours.

A Rude Awakening: The Killing of George Floyd

June 2020 was an absolute whirlwind. An awakening. The unfolding of events triggered by George Floyd’s brutal lynching has brought many things to the surface. Things that were hiding in plain sight. Over the course of the last 2 months, I’ve been scrambling to catch up. I’ve drawn up reading lists. I’ve committed to diversifying the media I consume. I binged watched Dear White People and 13th. I furiously Googled Angela Davis, bell hooks, James Baldwin et j’en passe. I read – and by read, I mean barely made it through – Eve Tuck and C. Ree’s A Glossary of Haunting (2013). I learned more about decolonization and indigenization. I read stories of colorism and told my own. I’ve had belief systems upended. I learned that there are no easy answers. I’ve tried to do my homework and in the process, found myself harboring a growing cesspool of anger towards things I should already have been vehemently fighting against.

In doing so, I’ve also felt incredible guilt, guilt for having been so complacent, guilt for having collated POC experiences with Black experiences, guilt for having the privilege of not having had to reckon that seriously with discriminatory social constructs earlier on, preemptive guilt for the complacency I likely will fall back into once anger subsides and momentum is lost.

In thinking about anti-Blackness in the United States, I’ve had to contend with this phenomenon being alive and well in Mauritian society. Many, mostly younger people (Gen Z and Millennials), have been having similar reflections and sharing experiences and perspectives. A quick glance inwards and around can reveal a lot of uncomfortable, often racist history. Yet our collective efforts still seem to pale in comparison with how we react to anti-Blackness elsewhere. If we’re capable of showing unbridled sympathy towards the unfair and unequal treatment of Black lives in the US, why can’t we talk about what’s going on in our own backyard? Why does injustice across the world somehow hit closer to home?

The Black Lives of Mauritius

Mauritius' racial makeup is the product of centuries of colonialism. Having no indigenous population, we were initially colonized by the Dutch, who brought slaves from mainland Africa with them. When slavery was abolished in 1835, Mauritius had an influx of indentured laborers hailing largely from India. Today, the ethnic composition of the country is still marked by early colonization, with roughly 70% of Mauritians being of Indian origin, and descendants of African slaves making up 25% of the population (source). With these two ethnic groups forming around 95% of the general population, it’s astonishing that Mauritius continues to be a favorable environment in which white supremacy persists.

In her paper, Decolonizing Creole on the Mauritius islands: Creative practices in Mauritian Creole, Gitanjali Pyndiah contextualizes insensitivity towards Black lives in Mauritius from a linguistic perspective. Citing Frantz Fanon, she explains that “the taboo around Creole languages is a reflection of an inferiority complex, visible in the attachment of the colonized for the colonial language” (Pyndiah, 2016). I would extend this observation to behaviors beyond language. We still largely buy into systems that were designed to oppress and exploit us. We are ensnared in residual neo-colonialism and this is apparent in what we see as valuable and what we seek to assimilate into.

Whiteness theory can shed additional light on why these neo-colonial constructs persist. Because “whiteness establishes a reality in which white people, as victims of their race as centric, do not experience the adversity of those with minority identification… whiteness [is] invisible to those who possess it, resulting in both intended and unintended otherization” (Ahmed, 2012). As such, whiteness “posits itself as the norm, from which all other things are deviations” (Alang, 2020). If we do not wish to be seen as deviations, as “other”, our best bet is seeking to embody the white standard as closely as possible.

Disappearing into whiteness takes a lot of different forms. It’s defaulting to English or French without thinking twice. It’s seeking to erase traces of our cultures in the way we speak, the way we look, the clothes we wear, the people we date. It’s using bleaching creams in hopes of wiping out unruly layers of darker skin. It’s systematically rejecting things that substantiate racial stereotypes. . And as Sahaj Kohli (POC counselor in training) accurately points out, it’s “[subscribing] to the belief that [our] worthiness is tied to [our] proximity to whiteness.”

Mauritian Legacies of Whiteness

In Mauritius, we are conditioned to move through the world in a way that makes space for white people. We might not be told in such explicit terms that white people are superior to us, but it is somehow understood. We don’t walk side by side, but on a diagonal. It’s understood that most white kids don’t attend the schools we attend, because they can afford not to. It’s understood that they own many of the large conglomerates that control resources and the redistribution of power. It’s understood that as a brown or Black person, you need to rise above your race and the limitations you often inherit to sit with the cool kids. If you manage to join their ranks, you’re cool by association. You hear the same couple of white last names in any conversation where corporate land ownership is mentioned, names that become synonymous with power. You grow to not question, but internalize these notions, such that they mesh with your worldview and reflect on your perceived place in the world.

During a coffee catch-up with a female POC friend recently, I felt the urge to bring race to the table once we were done exchanging pleasantries. We were very quickly able to identify our experiences with anti-Blackness in Mauritius, both as victims and instigators. As brown women, we both acknowledged having been on the losing and winning ends of anti-Blackness. This was probably the very first time we were in a space where we openly exposed our biases and the exchange was equal parts liberating and aggravating; it’s painful to have to think of our own contributions to systems we don’t believe in and are victims of.

Aqiil Gopee’s urgent and informative note reads like recurring dreams we’ve collectively had but never acknowledged except to ourselves. He eloquently recounts our colonial past, while delineating white but also POC-enabled racism against Black people. He also goes on to expose the very obvious, yet rarely addressed dichotomy between the small percentage of white people on the island and their potency: “White people might represent a numerical minority in Mauritius, but they still hugely benefit from the treasures colonialism begot their ancestors.” He calls out our active participation in colorism, and our responsibility as POC in perpetuating interpersonal and intrapersonal racism by seeing ourselves (at best) as peripheral to white people, as the self-effacing sidekicks to white protagonists in our own stories.

But the most devastating and shocking accounts of all (in recent memory, at least) has come from Ariel Saramandi, who offers a peek inside overt anti-Blackness in a Franco-Mauritian context, easily identifying neo-colonialism in Mauritius. She describes her unique experience of navigating life as a woman of mixed descent, privy to the social advantages her white father benefits from, as well as the discrimination her Black mother continues to face. Her account echoes an all too familiar feeling: “we imbibe racism until we cannot see the world in another way.”

Brown Fragility and Intrapersonal Racism

The common thread I’ve since observed in many POC pieces on anti-Blackness is a feeling of complicity and guilt. While explaining – and perhaps coining – “Brown fragility” as the forgotten counterpart to white fragility, Rochelle Picardo accurately depicts the discomfort we feel when being faced with our own biases. Because we so badly want to be good, because we can’t see ourselves as good if we’re racist, acknowledging our racial biases is uncomfortable. But as Picardo continues to posit, “this notion is not only untrue, but it is harmful. It downplays that other people of colour can — and do — play a role in defending the white status quo that is actively oppressing BIPOC.”

Allyship beyond the performative is imperative. It’s unreasonable to think about dismantling systems if we cannot recognize how we benefit from them. We cannot urge others to uncover their implicit biases if we don’t do so ourselves.

I’ve done some digging and thought it necessary to put some of my own biases out there. Because it’s time. Because hopefully, it’ll be liberating. Because I believe many of us are out there acting on neo-colonial notions we badly need to dislodge.

So here’s a non-exhaustive list of thoughts I’ve had and things I do that a) feed into intrapersonal racism and b) are directly or indirectly anti-Black:

– Hide my face and body from the sun

– Compare skin tones with other brown people to see who’s fairer

– Feel better about myself when I haven’t tanned and people notice it

– Feel shitty about myself when I tan

– Feel less than when I see my boyfriend’s fairer body next to mine

– Feel better about myself when I’m around darker people

– Subconsciously hold more space for white people and stories

– Feel small in overwhelmingly white spaces

– Aggrandize my Canadian (potentially white) identity and belittle my Mauritian one

– Use filters on Instagram that “correct” darker patches of skin

– Internally reject social media images that don’t fit a slim and largely white ideal

– Feel an increased sense of worth when given attention from white men (as opposed to men of color)

– Defer to white people’s opinions and knowledge (assuming they know better by default, when it comes to everything under the sun)

– Whitewash my stories and experiences so I don’t come across as “foreign” or “exotic” (as a brown woman living in Canada)

– Internalize whiteness as standard, as normal, as ideal and hence seek to tone down “cultural” aspects of my being

– Subconsciously feel the need to prove myself in front of white people

In reflecting on my painful contributions to white-centrism, I’ve come to realize that this often reads as “I may not be white but at least I am not Black”. I find myself caught between inferiority and superiority complexes, grappling with a flimsy sense of self that longs to be centered.

If there’s any one thing I’ve slowly internalized in my readings and conversations over the past months, it’s the notion that racism is fundamentally systemic. That the system isn’t broken, because it was built this way. We have to unlearn our understanding of racism as being strictly behavioral, because this notion addresses a symptom while glossing over the cause. Even if we haven’t explicitly expressed racial prejudice towards people different from us, we’ve either been benefitting from the system or been unfairly penalized by it. Sometimes both.

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all road map on how to rid ourselves of our biases and decenter whiteness. We’re all moving along at our own pace, trying to keep up, unlearn then relearn and fuck up a little less. A lot of good people have been putting in the work though, by sharing their stories, by creating content for change, by supporting BIPOC businesses, by listening, by educating, by providing learning spaces and by retelling history from an approach that isn’t white.

It still feels like there’s a lot of catching up to do – and systems to rethink and upend – but what I can commit to, at this point, is a relentless willingness to improve, to listen, to examine my biases, to educate myself. I plan to continually think of the systems I’m a part of: who benefits from them? Who do they oppress? I want to be the ally who shows up, warts and all.

—

Here are some resources that have been helpful in guiding me as I seek to decolonize my gaze, deconstruct my biases and de-center whiteness as a Canadian-Mauritian woman of color:

Decolonizing Creole on the Mauritius islands: Creative practices in Mauritian Creole

A Note on Brown Fragility, and a Call for Allyship

A couple of Instagram accounts worth following:

Sheerah Ravindren - Hairy Darkskinned Tamil Dravidian Immigrant Womxn

browngirltherapy, initiative by Sahaj Kohli, therapist in training

BIPOC designer, recently launched the online course "Unpacking Internalized Racism"

Spicy Devis - Decolonial feminists, adding Brown experiences to your White feed

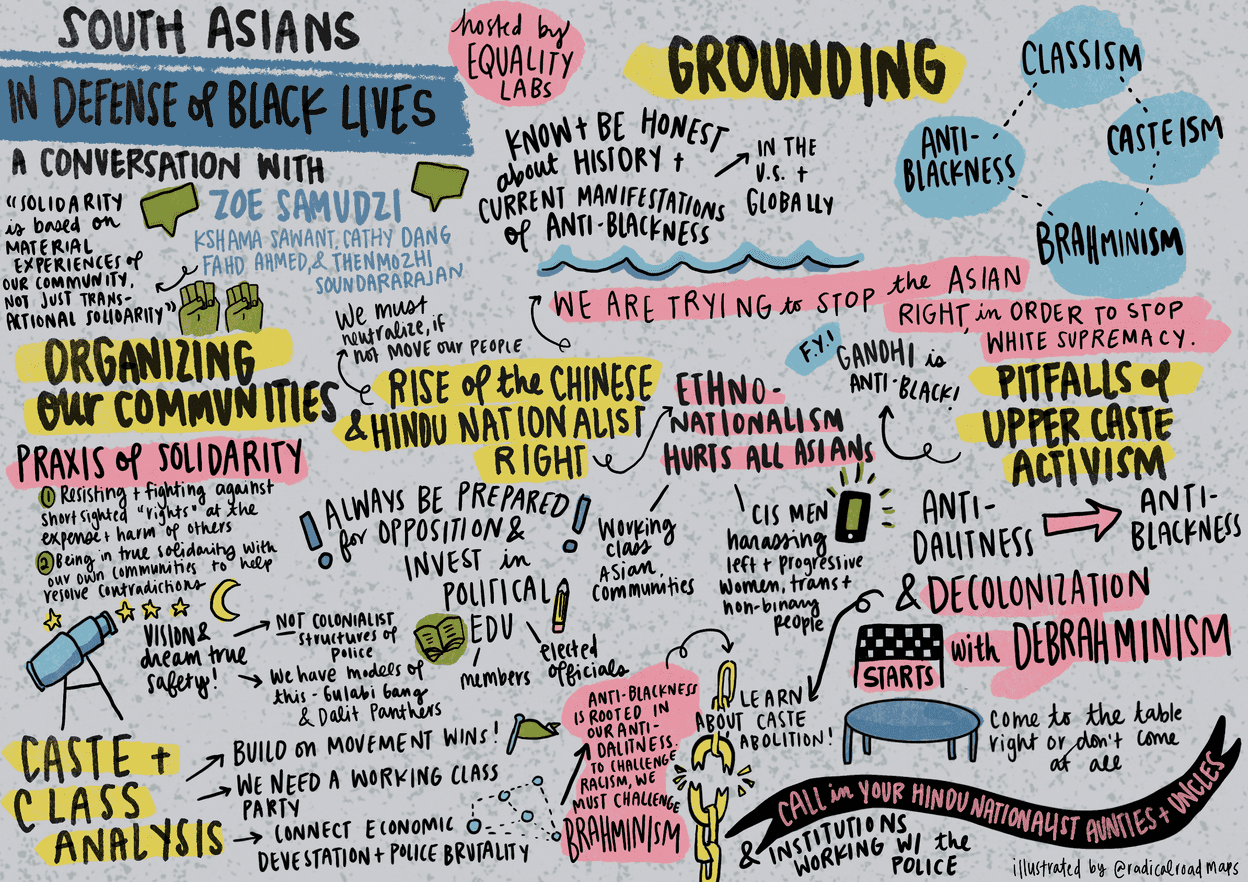

**This article was originally published on the author's blog Litlamig and the cover image is art by @radicalroadmaps featured on Equality Labs - South Asians for Black Lives, a power-building organization that uses community research, political base-building, culture-shifting art, and digital security to end the oppression of caste apartheid, Islamophobia, white supremacy, and religious intolerance.