Over the past year I lost a form of love but I was showered with another. Ladled in steaming bowls of Laksa, roasted in English root vegetables; a residue of stubborn earth remaining despite a stellar scrubbing. In pools of butter, yoghurt with garlic, dwelling in the richness of Turkish eggs; and a Sunday ritual - always based around food - knees pressed around a too-small London table, knife crunching through the skin of roasted chicken. It was an intangible but omnipresent love. Food crafted by my friends did more than heal me from heartbreak. I realised they were satellites, not lumps of lonely metal singular in their orbit, but Sputniks, travelling companions. Separate but whole and fully formed units choosing to dance in synchronicity. Sharing food was a recognition of the plurality in the lives I could choose to orbit with. They were, as described by Kath Weston, the family I chose.

Incidentally, I think food can build a family, not to diminish blood ties but to question what types of relationships we benchmark over others. Families or kin are often chosen in queer communities to neither reject blood relatives nor strictly ‘choose’ friends as family; this rather encompasses a larger rejection of kinship or the ‘nuclear family’ which pathologises unconventional forms of sexuality and love (or instead, in becoming acceptable necessitates ‘queerness’ becoming the salient part of the individual’s identity). Chosen families are forged of love, friendship and biology, but most of all they offer forms of visibility and acceptability informed by knowledge that far more fluid forms of gender identity existed long before they were quashed by the cages of colonial gender binaries.

Western folk models of family are founded on the notion that blood is thicker than water, however, consuming food essentially entails the transformation of the latter into the former, it makes those that are unfamiliar familiar. This is recognised cross culturally where familial structures are less rigid, far more processual: The Malays of Pulau Langkawi draw up their lines of kinship through the idiom of fostering, where sharing food creates ties of blood and birth, just as much as nurturance or sexual procreation. Generosity of food brings strangers from outside familial structures and food cooked on the hearth acts as a creative force to produce new emotional ties central to processes of being ‘together’ whether through blood, milk or rice.

Outside of Western folk models, food is a wider tool of sociality which builds kin relationships and often takes eminence over biological relatedness. The babies of the Beng people of the Côte d'Ivoire are not believed to be humans, raising a child is rather a process of familiarising yourself with a divine stranger from the afterlife. Unsurprisingly, questions of biological relatedness figure small in a baby’s journeys emerging from ‘Wrugbe’ (the afterlife) where they are divinely multilingual beings. Raising a child is a process of familiarising yourself with a stranger from the afterlife, and adults listen rapturously to the babies’ babbling for pearls of ancestral wisdom. Unsurprisingly Beng babies are ‘alloparented’ (the name for childcare provided by individuals who are not related in blood) and the babies experience the breast of many women as a formation of sociability as well as nourishment.

Cooking and eating together has an affective and communal force, to break bread with another is an experience of sisterhood or brotherhood, of care and connection. However, as a precondition to the advent of capitalism, individuals in industrialised nations are often estranged from broader conceptions of how to be together in non-biological kin formations. It runs as so: the nuclear family naturalises the unpaid labour of cooking and care (hiding the labour power this facilitates in the wider economy) which if not devalued or dismissed is certainly side-lined as insignificant belonging to the naturalised and private realm of the family (you needn’t look no further than the vastly overworked and highly skilled chef’s salary as a reflection of how this ideology travels).

Feminists have, of course, come up against quite a fight whilst trying to dismantle this; an essential harbinger of creating free labour power in industrialised nations is predicated on the naturalisation of European and North American cultural formations of family (most commonly the nuclear family) to which rigid gender roles are crucial. Sylvia Yanagisako describes this as the ‘domaining’ inherent in late capitalism where the artificial distinction between the economic and domestic sphere separates emotions, affect and sentiment, and distinction between the domestic (the realms of kinship) and the economic inform the assumption that domestic labour is not a form of social reproduction (in Marxist terms this refers to activities which reproduce and allow for the labour power essential to capitalism).

Feminist agendas ardent but exhausted bristle at the connotations around cooking for they are often cloaked in the limited garb domesticity foists upon them. But it is not the act of cooking which is burdensome but its relegation to the private sphere where women’s free labour is naturalised.

It is true that for many (especially women), cooking is a slog; a chore; a relentless rhythm of unrecognised servitude. Often an act of love but also an undeniable reminder of the domesticated femininity women are benchmarked against. In other words, cooking becomes a signal for women’s diminished status where domestic chores are as personal as the contours of the feminine mystique, far from the ‘real work’ of economic relations. However, although cooking food is labour, to reduce it to just this is a disservice. I grew up in a house where love was spread like butter. Although sometimes the latter was too cold, the bread too soft, cooking held significance, something more enduring than its definition as only a form of reproductive labour (all the domestic work associated with caregiving, cleaning and cooking).

In writings of culture, cooking always holds eminence. The seminal anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss situated his grand theory of culture in the everyday rituals of cooking. The latter, he argued, afforded humans with the unique ability to transform nature using stones, fire, pots and pans; the artefacts of a culture, bestowing humans with the characteristics to transform nature to culture - and achieve what is arguably is the biggest distinguisher between human and non-human animals. However, I like to think of cooking as just as seminal but somewhat less wrapped up binaries around nature and culture, nor the answer to the ubiquity of human culture located in my favourite Le Creuset pot. But rather cooking as a form of often overlooked praxis

‘Praxis’ is a practice or custom translated into action; the practical application of a branch of learning or theory. In Marxian philosophy, it is the notion we must interpret the world to change it, crucially this transformation of subjectivity is first and foremost through practice and human action. Although language is pivotal to such a process, ideological roadblocks run rife when trying to imagine alternative subjectivities with words alone. The linguist Saussure explicates this describing language as communication which cannot convey truth, but is rather a signifier for that which the speaker chooses to signify. This signification is drawn in the form of historic concepts belonging to a larger project of colonisation, capitalist expansion and oppression. Cooking is by nature a practice, imbuing it with the ability to shift subjectivity, feeding and nurturing alternative ways of doing or feeling.

Cooking is a movement of creation rooted in everyday action. In other words, cooking is praxis. It is magic which creates and sustains us, which transforms the inedible to the delicious. Crusts of (much fretted over) sourdough dipped in Zatar and olive oil taught me that friendship and sex can be many different things which are ultimately more complex and satisfying. Even if they were only crusts, they showed me my grief was not for another person, but for myself and all the love that had been poured into the places which could not contain it. Food helped me learn honesty, communication and connection can be found in the relationships which are least obvious.

Sharing a meal is an everyday experience of togetherness, a nod to our most basic and shared experience of vulnerability, the need to consume food to sustain ourselves. Cooking has so much more potential than its condemnation in this brief moment in our current capitalist epoch, it is a practice which refuses in modernity to dwell in the murky realms of the domestic sphere; most importantly it challenges the domestic spheres existence in the first place. It requires imagination and empathy, eliding categorisation, spilling out in questions which make light of the very notion that our lives can ever fall into neat distinction. What does the person like to eat? What food is home to them? What food formed their bodies? And of course, the anticipation of how they will enjoy the food created for them, and the shared experience of consuming it. Cooking and eating is giving and receiving pleasure.

Friend’s food also showed me a new experience of being together. Seemingly small, quiet and understated gestures of care and cookery helped heal me, in fact, they continue to. It is not coincidental in the Autumn I took the class of the late great David Graeber, his work (like his character) unrelentingly optimistic, highlighted the utopic spirit in everyday acts of sociality in workplaces, schools and institutions; everyday acts socialism hidden in plain sight – cooking in this instance. However, what influenced me the most was Graeber's focus on the phenomenon of play. He insisted all animals play (ants to inchworms to dolphins to humans) with no scientific or rational explanation, but rather just for the pure frivolous fun, antithetical to the logic of the normalised ideal of the rational and market-driven actor. In acknowledging food and cooking as more than simply the fuel of capitalism, we can begin to understand it as a form of resistance which carves out new ways of being together, and one of the ways we live joyful, playful and frivolous lives together, because why not?

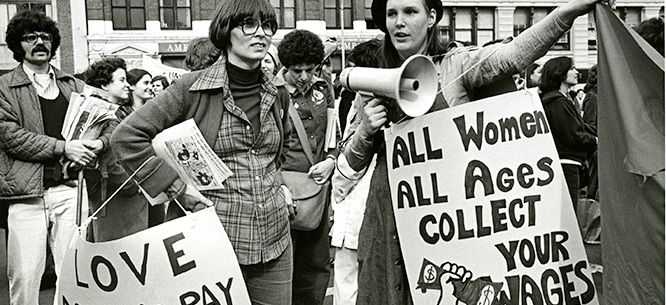

Cover photo: Wages for Housework supporters at an International Women’s Day march in New York City, 1977. Photo © Freda Weinland. Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard: Dissent Magazine