Esraa Warda is a performance and teaching artist who preserves and transmits traditional Moroccan and Algerian dance forms through movement workshops and interactive performances. A young talent of Algerian origin, Warda is a community-taught dancer under the mentorship of women elders in her family and artists from Morocco and Algeria. She is a firm advocate in the power of intergenerational transmission, women-led traditions, and decolonizing euro-centricity, Orientalism, and oppressed bodies in dance. Esraa Warda has graciously offered her time and generosity for this interview in which we discussed her upbringing, the asymmetrical boundaries of modesty, the male gaze and the hchouma culture.

This conversation is published in 2 parts.

. . .

Amina: How do you define yourself and what brought you to dance as a vocation—as a lifestyle?

Esraa Warda: It’s hard to explain. I feel that there are two types of artists—those who are born dreaming of becoming an artist, spending their lives chasing after it. There are those who never envisioned becoming artists. It came onto their plate. A lot of Chikhates in Morocco would tell you the same story, that they had no plans of becoming dancers.

My first dances were Algerian dances. I was born in Brooklyn, New York, and I was different from the other kids in my neighborhood because I liked world music. I listened to R&B, Hip-pop, Rap and so on, but I also made my own Rai CDs. I used to travel to Algeria throughout my childhood, and that developed me into the person I am. Dance and music played a significant part in my imagination. My family had a very conservative opinion about dancing and music in general, and my father was far stricter than my mother. I remember I used to have Rai parties with my American friends. I would teach them, and we would dance together but never when my father was there. I have never, until this day, danced in front of my father.

Algeria was the first place where I danced. I was about 12 years old, and I had stayed there for a long time. There was a gathering in a small living room and my uncle was the first person to say “hey, get up and dance”. I didn’t know anything about dancing at the time. The music was Algéroise music which is Andulusian music, specifically from Algiers. I didn’t know what I was doing. However, that specific moment shattered many ideas I had—because in Brooklyn, New York, I was hiding music from my father, turning it down when he’d come, pretending I was doing homework. And there I was, in Algeria, having my uncle be the first person to ask me to dance. That particular moment introduced me to the idea that: patriarchy is not real, it is a concept. Patriarchy was not a physical barrier because if it had been, my uncle would have never asked me to dance. Nonetheless, patriarchy causes physical issues, yet I realised that it didn’t have to be my reality since I had gone somewhere else and danced in front of men. I soon realised that it was something that was specific to my dad and people like my dad.

It was an awakening: dance was associated with shame— a reality I didn’t process only as I got older. After that first initiation, I would get invited to weddings, parties, and celebrations every year when I went to Algeria. People loved to bring me and dance, and we’d have dance competitions, and my family respected me as a dancer. As a teenager, I used to hang out at “Palm Beach”, a cabaret which I am sure every Algerian would know. Palm Beach as in Palm Beach, Florida. The place was a disco on the beach. Only, it was split in half by a rope on the sand. A side for ‘families’ and the other for men, based on the premise that the men were there to have fun, smoke weed. And that no one wanted to mix that with family vibes.

Palm Beach was one of the few free beaches in Algeria at the time. Public beaches were poorly maintained and were dangerous. And the only people who could go to private and safe beaches were wealthy people. It was a class problem. Palm Beach developed my ultimate dance techniques because I was dancing on the sand with my cousins. Yet I couldn’t dance when my mom was there, she hated it. Since it was a free beach, all the men who would come from other neighboring towns, would come watch girls dance. We were on the sand, and they would stand on the boardwalk, or on the water and just watch. And so, me and the other girls had an audience every night.

Palm beach was the place where I learned about the Cabaret lifestyle—it was a Cabaret but situated publicly, and outside. It was controversial, and got targeted by the islamists in the 1990s. It was bombed during Algeria’s civil war, when the government was run by the Islamic Front. They didn’t want people gathering there, and dancing. It was also seen as a “low-class” space—where men and women would dance together, mingle and where everyone can see you. There was Rai music non-stop, sex workers and many other cabarets along the sidewalk.

This is where I learned about the harmony of contradiction in North Africa and Algeria. It was considered as Western space because everybody was wearing a maillot (swimsuit), 2 pièces—where girls are with their boyfriends, where everybody is drinking. It was also a place which men couldn’t handle. It was outside of their comfort zone. It was overwhelming.

Amina: As if they were excluded from it but wanted so desperately to be part of it, even if just to observe.

Esraa Warda: They were obsessed with it because traditionally women would only dance among one themselves. Suddenly, women were dancing publicly. It sounds crazy now that I think of it.

Amina: It sounds like a radical place.

Esraa Warda: It was, but it wasn't a fancy place. It had a bad reputation. There was a lot of gang violence. I used to see people sitting at the table next to me getting stabbed in their legs. It was an anarchist space. This Cabaret was not legal. The people who were running it took a piece of sand on the beach and had no license. They had to fight everyday with the local folks at the beach to protect their territory. Now it’s gentrified, it doesn’t exist anymore. They replaced it with luxury hotels and no music is allowed on the beach. I don’t know what it looks like at the moment because I haven’t been in Algeria in 7 years.

I had to provide you with context before answering your initial question. At this point, dance had become a huge part of my identity however I spent most of my teenage and adult life trying to figure out who I wanted to be. I juggled between wanting to go to college, studying political science, hesitating whether to become a lawyer, only to realise that I didn't want to become any of it.

I always found myself surrounded by artists. At 21, I was hanging out with big stars from all types of very famous Gnawis, and other big hip hop stars in New York. I loved being around music and artists. But something didn’t feel right— it just didn’t. I felt that the artists’ domain was all men who thought they were gods and that women sat gladly around to watch their mediocrity.

Making dance my life was like alchemy. A purely spiritual accident. I never planned it. I believe in Maktub: that some things are written for you, and time brings you closer to them. I can’t tell you the exact moment when I wanted to dance. There were little seeds that steered my dreams. At the time, my friend and I were the co-directors of a traditional Arts program at an Arab-American Center in New York. I was hiring a lot of Arab artists to teach workshops to children. I think I may have gotten the idea to teach my own dances by managing that space.

One day, I woke up realising that I had more than 20 years experience of dancing North African dance and, yet I never saw it or perceived it as a talent. Why was that? I never considered it an art form. I started in down-town Brooklyn hosting workshops for free, and people started to come. I wasn’t trying to make money, it was for fun. I started running classes and hangouts, parties with all ethnicities in New York. The class became very popular, completely by accident. Even at that point, I wasn’t planning to become a teacher, it’s as if people picked me to do this job. I realised I needed to accept it. It was my reality, and I needed to ease it into this destiny. Ever since, I dedicated my life to dancing. This is my only job, this is how I pay my bills, feed myself and take care of myself. It felt as if the whole world was waiting for me to do it.

A few years back I did a performance in Cuba. Someone took a 45seconds video of my Chaabi dance performance and it went viral. I hadn’t planned for this career but it’s perfect for me. It’s my partner in life.

Amina: I happen to be in a liminal space and I am learning a lot from what you’re saying in terms of taking what you’re given and believing that you can do it and go beyond your own expectations and everyone’s. And I love it because we live in a society where thinking of one’s career is a project of strategy, fake networking. With art, as I am learning with you, shouldn't be forced.

Esraa Warda: It’s so interesting when things are just meant for you. Stuff just flows. I started getting connected, and receiving attention from all over the world, I didn’t have a strategy and I didn’t care about making one. I’ve been living in Harlem for 10 years now and I just hang out on my stoop, minding my business. It took so long for me to believe that the talent I have is real, that it is worthy despite our North African people thinking that it is not an honorable job. I refuse to think as such—my dance is my duty and my job. This is my Maktub.

Amina: Why do you think that being a dancer is stigmatised, and seen as not an honorable job to do, in “North-African” culture? I think it goes back to me really wanting to ask you to define the patriarchal gaze, in your own words and how you perceive it to be.

Esraa Warda: It’s something that I have been battling my whole life. I was thinking yesterday that for my whole entire life I have been labelled as a whore and it’s been a serious problem for me. When I was in sixth grade, all the boys in class started a whole trend: getting everyone to call me names. I remember that when I told my teacher, she started crying in front of us, reprimanding the whole class. It started that young, at 12 years old when little boys were calling me a “slut and “a whore”. And when my father was scared of me becoming a “slut or a “whore”, he’d become overprotective and strict with me as a kid: not allowing me to wear what I wanted. I was asked to cover my body with long and large clothes. I was not allowed to wear make-ups, or earrings so that I wouldn’t draw men’s attention.

The patriarchal gaze has to do with a woman’s physical presence. We’ve learnt that a woman moving in public means that she is now a public discourse, that because she has the audacity to be outside, publicly, her body is immediately a public property: that it belongs to the rest of us. That her body can be touched, that she can be followed, called names. Bodies and modesty have been liaised with worth and respectability. Even if you are covered up and dancing publicly, you are considered immoral, without values.

I think there is a co-dependency between religion, culture, tradition and nationalism. They have been mixed into one thing, while in reality they are separate. You can be a Moroccan or an Algerian who enjoys folklore and traditional music, and not be patriotic or nationalist about your country—maybe even critique your governments or country's systems - and at the same time maybe even be an atheist. The creation of boxed and rigid has failed us in seeing how multidimensional people are. There are too many binaries. For instance, because a woman is wearing a shirt that shows some of her breasts, she is whore— a woman not worthy of respect. While in reality, this is a heavy burden to carry. I genuinely assume that women do things because they want to. At the end of the day, these are our bodies, yet what we do with them is always put into question by other people. The problem with this idea, and in Algeria in particular, is that it has such dichotomies for women. Either you are a Qahba قحبة (whore) or Bent famili بنت فاميلي (respectable girl): No options. Either you’re qaria قارية (educated) or mezwja bdradi مزوجة بالدراري (married with kids) at 18 years old. As if they were only two options for a human population. This is even more particular to women. Throughout my life, I have always felt that I had to be one of these two things, only to later realise that I am neither. There are many layers to people’s identities and personalities.

I am somebody who loves Cabarets. I grew up in Cabarets, I learnt to dance in Cabarets and I am also college educated, I went to a great college in New York. I love traditional music and the traditions of North Africa. Sometimes I wear leggings, sometimes I wear Jellabas. As you see with the younger generation, people are embracing this multidimensional spectrum of being. It's not only about gender expression or sexuality, but rather about personality and interests. We know that back home [ Algeria ], there are many limitations about being open, not fitting one category. I am a good example of that. The reason why I mentioned that I love cabarets is not because I think those things don’t go together, they do. In typical mentality, if your girl hangs out at Cabarets, she is not smart. She doesn’t respect herself. This is annoying because men are constantly expecting us to be respected by them but we don’t really care. They use these excuses and oppressive norms to reveal how insecure they are.

I was in Brooklyn, New York and yet my father didn't want me wearing tight clothes so that other Arab don’t think of his daughter as “slutty”, but who the fuck cares? It’s the same idea that I mentioned: Patriarchy is an invisible enemy. You don’t see it there but it controls the way in which you express yourself. I still have a hard time expressing myself openly and being creative because patriarchy shut that down for me so much when I was younger. At 9 years old, I had to worry about not having old men looking at me or be deemed immoral because I dance.

A lot of it has to do with fantasy. Men fantasise about us because, even though Morocco and Algeria are not the most religiously conservative countries, there is sometimes gender segregation in weddings for instance. Some men will tell you about their fantasies when they were 6 or 7— when they went to a Hammam, or 3erss* (wedding) with their mothers where they got to see women dancing. These fem only spaces are such a fantasy for Maghrebien men. They try to infiltrate the spaces that don’t include them. They hypersexualise feminine spaces. These are our own spaces that are still analysed by their patriarchal gaze since they are not invited.

Due to some of the conservative values we grew up with, women are expected to be modest, yet our idea of modesty is screwed. Here is my example: if you try to look up Arab porn, and this is based on my own research, it’s not even hardcore, it’s not x-rated stuff, not that it is a category, some of it is just women dancing in tight dresses, showing a bit of cleavage and their underwears - Expecting "modesty" from women is about control.

Men fantasize about women so much that women dancing in tight clothes, in their underwear, or showing a bit of skin would be considered porn. On these websites, women dancing is pornographic —Isn’t it crazy? These are videos which are also probably filmed without women's consent. Men are more angry about women making a choice to consensually dance publicly without inhibitions, more than watching women dancing or being sexual WITHOUT their consent.

The public versus the private spaces is a significant debate to dive into. A lot of people have mixed weddings, in more modern quarters. And so part of what I am talking about applies to the more conservative parts of North Africa. This is why they love Chikha Tsunami and Chikha Trax because they wear traditional clothes, breaking and pushing traditional limitations. That is what North African men fantasize so much about. It’s hard to explain. I think that is why artists like Chikha Tsunami are so controversial because she is just being herself. She is an expert in her music. She is educated about it, and has learnt from older Chikhate. She does things her own way and she is proud of what she’s got. North African men are more obsessed with you shaking your ass in a takchita, than wearing a mini-skirt and walking down the street, because you are doing something "immodest" in the confines of modest and traditional norms. They are also obsessed yet uncomfortable with our Jedba, our trance— one of the only times we are "tolerated" to be wild in public spaces.

Amina: Part of what you said made me think of how much effort we have to make to unlearn the patriarchy we’ve internalised. I think it’s a work in progress for a lot of us.

Esraa Warda: You know sometimes I just want to go in the streets and scream. I really think about the way that I dress and the way that I move. I noticed that I have internalised so much shame, I don’t even sway my hips too much. I don’t want to get too much attention when I am walking. I had to change my entire wardrobe because of street harassment here in NYC. It is hard not to be defeated, not to become silenced and quieter. The only place where that doesn’t happen is when I am dancing. It’s the place I make sure that I am not quiet—and even that is hard. The first few years when I started dancing, I couldn’t dance in front of people from the community, Arabs and North Africans. Even when dancing in Morocco, I’d get a look from someone when I am on stage. These looks can make you uncomfortable. People stare with judgements: about who you are; who you have sex with; if you have sex; if you have a lot it. That’s the power of dance, to have people imagine what you could do, and what happens in your private life.

Amina: That resonated deeply, and even when I think of Chikhates الشيخات in Morocco, it’s almost as if they are reduced to that layer of their identity as dancers and as you said, the pre-assumptions and judgments fill that space. I doubt anyone would ask a Chikha about who she is, because she is arguably“known” — معروفة، باينة…

Esraa Warda: We treat women dancers and artists like caricatures and cartoons, as if they’re not fully developed humans.

Amina: I think you are changing that scene and how things are being done, mindset by your presence, your voice and your art.

Esraa Warda: I think a lot of people are, a lot of modern dancers are doing the same.

Amina: From the interviews that I’ve read and what I also understand through the spaces I grew up as well, dance is stigmatised. Are there specific historical turning points which one could look back at to understand the shift. In other words, I want to understand with you the mechanisms through which the “hchouma’ culture has been put in place (Perhaps it’d be good to distinguish between hchouma versus stigma)

Esraa Warda: The Hchouma culture ثقافة الحشومة is the number one cultural terrorist in a North African person’s life because it’s based on the idea that validation ought to come from people as opposed to from inside one’s body. That through your clothes and actions, you are meant to represent an honorable, respectable, and “marriable” woman. You then spend your whole life trying to prove that you are that. That is a life in misery or, else you end up not giving a fuck about these rules, and people would end up calling you a whore anyway. I’ve taken the second road obviously, but Hchouma comes from the shame of being free. I think of Freedom very often: when are people going to be free? For instance, Ana 3rida عريضة , I am a big girl, big hips, big big butt, big koulchi. When you are a bigger person, the amount of sexual stigma towards you is multiplied by ten. You take up more space and that is more debilitating, which is against what women are supposed to maintain: small spaces so that we are less invisible and not talking too much.

READ PART 2 / to be published on May 15th.

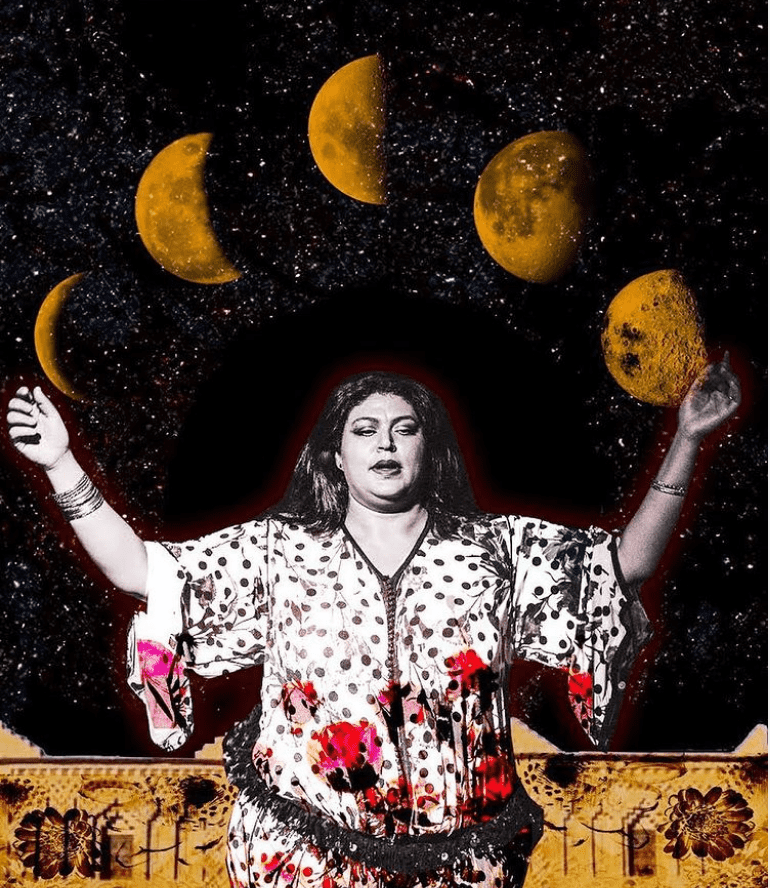

Photo Cover Credits: “Cycles” —Art by Mariyem Moutaouakkil