The Initial Birth—

The Decoloniality Reading Circle began in the Old Anthropology Library, on the 6th Floor of the Old Building, Portugal Street, at the London School of Economics and Political Science in November 2019. It gathered undergraduate and masters students from various departments: Anthropology, Psychology, Gender Studies, Development, Sociology and Public Policy. The circle was birthed with the aim of providing a space for alternative knowledges, and ways of seeing the world: an attempt to circulate a correspondence between our marginalised intellectual ancestors and ourselves. We sat in the presence of decolonial touchstones; from Hanna Arendt, Frantz Fanon, Eve Tuck, and Walter Mignolo, to Gloria Anzaldua and Achille Mbembe, navigating paths far less well trodden, of alternative intellectual genealogies of feminism and antiracism, and manifold other forms of oppression. We created a space where we could move beyond the political labour the academy demanded of us, insisting instead that racism and sexism were more than what we were thinking or feeling. We created a community not defined as ‘just doing’ identity politics, but instead as something more expansive and ambitious. Once released from citational chains preoccupied with familiarity and repetition—for these are ill-equipped to navigate racism and sexism, only able to acknowledge them through grievance— we found the intellectual space to breathe and explore what sort of world we wished to build. We pondered and wondered about Decolonial Praxis, Borders, Citations, and also questioned who the decolonial option was for? As weeks went by, we were also joined by LSE Anthropology academics, allowing for a much broader conversation and conviviality, horizontal learning, and co-understanding, as we continued to weave our personal narratives into much larger events embedded in colonial realities that often stripped us of the right to belong.

The circle transcended academic discussion to become a space of hospitality and sharing: chocolate, fruits, and snacks. We also shared parts of ourselves: how we navigate a neoliberal university, racism, and out of-placeness. We awoke to how we could dismantle knowledge to transform a world built to only accommodate certain bodies, and to care for one another in the process. And we wondered often about the likelihood that the stranger we just shared the lift with might be the person who our activism and politics will be against in a few years time, as they go on to become directors at the World Bank and the IMF, continuing to perpetuate world inequalities.

A Transition—

As the university shut down due to the COVID 19 crisis toward the end of the academic year, our discussions, like our lectures and seminars, moved online. Zoom became our new sanctuary every other Wednesday, and the conversation grew larger. The reading circle began welcoming avid readers beyond the LSE. We moved from an institutionally- and geographically-contained physical group to a Whatsapp group with more than 17 international numbers, and about 72 participants, with an average of 14 participants per bi-weekly discussion joining from South Africa, Morocco, The United States, France, Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom, Scotland, Switzerland, and Egypt, among many other places. As it had begun, the reading circle continued to operate horizontally: for each session, a different individual would suggest a reading and facilitate the discussion. As the conversations became more transnational we witnessed the forging of new solidarities while elsewhere the statues of colonial figures found their ways into the abyss, and protestors walked out in the streets of Minneapolis, Sydney, London, Seoul, Rio de Janeiro, Tehran, Porto, Hong Kong, Auckland, Zurich, and many more cities across the world claiming space, the right to territoriality and freedom. These new solidarities helped us ground ourselves even more: our silence shall be no longer, our anger and desire to see change, to be change, is not only a horizon but a present in which we choose to exist, as academics-to-be, as policy-makers, thought leaders, and radical feminists.

Why a Decolonial Manifesto?

A decolonial Manifesto is our roadmap. It carries what we have learnt throughout this past year: conversations and dialogues which are timeless and boundless. They are a home to our imagined hopes, and we choose to move forward by sharing our learnings. By choosing the decolonial option, these learnings have become or were already part of our realities—by default.

1.A Decolonial Manifesto Listens to What Bodily Sensations May Teach Us—A decolonial manifesto asks us to listen to our sensations and what they may teach us. To engage with our bodily archive with gentleness and curiosity is memory work, speaking to times when our bodies have not felt at ease in the world, awakening a body that has had to numb and contain its essence to survive. Sensations, as described by Sara Ahmed, are sensational in how they relate both to ‘faculty of sensation and to the arousal of strong curiosity, interest or excitement’ (Ahmed, 2017:22).

A decolonial agenda looks to make spaces welcome for the bodies who are made to feel ill at ease in the academy and the wider world. It recognises that an impulse to move, to fidget , twitch and shuffle is a valid response to a body thrown into a world where it feels unwelcome. But it also sees the desire to move as a latent form of resistance, a sensational call to arms. Sensations act as new pathways outside of citational chains: they are new building blocks which dissipate shame, accepting our emotions, our bodies, our anger as valid and fruitful. A decolonial space welcomes bodily forms of knowing and acknowledges any space is as much ours as anyones: that the human is not defined by man, that the personal is always political.

2. A Decolonial Manifesto Is Committed to Continual Questions Rather Than Simply Statements, Thoughts, Reflections or Facts— A decolonial space is grounded in questions more than it is grounded in statements, thoughts, reflections, or facts. Entering the paradigm of decoloniality requires the critical and continuous questioning of what we know, how we know, and why we know. When we step into the decolonial space, we step outside of the insides of ourselves—not to lose our connection with the latter but to regain touch with it.

Decoloniality calls on us to question the construction and deconstruction of ourselves and the worlds around us from places of curiosity, radicality, nostalgia, anger, excitement, humility, purpose. Subjectivities, thus, are not demonized; they are recognized, understood, expressed, utilized, even destroyed or amplified. The decolonial pursuit of questions is not a pursuit of answers per se, but a pursuit of more questions: those unasked and/or mis-asked. Decolonial questioning examines learning as epistemology, using unlearning and relearning as meta-epistemologies.

3. A Decolonial Manifesto Takes Activism to Academia, Building A Movement Integrated and Congruent With Wider Workers and Civil Society Movements— In addressing the argument of bringing academia to activism, it is important to equally take activism to academia. This may sound like a truism, but in postcolonial contexts where multiple epistemologies exist, it is critical that we utilize activism and civil society movements as tools to produce more inclusive theory within academia.

Truly, knowledge dissemination methods need to be diversified, but there is value in utilizing activism to create decolonial theories. This also calls upon cross-collaborations between postcolonial groups while accentuating our refusal to split between that which is economic and social. Workers’ rights are our concern. The justice for cleaners movement at the LSE, for instance, saw the involvement of many of us. Our activism must be truly taken outside the academic space.

4. A Decolonial Manifesto Dwells In A Space of Activism Which Is Not Defined By Nor Reproduces Identity Categories— It is not about where one is but where one dwells. Dwelling in a thematic means that you unsee borders, that you undo the ethnocentric nationalist knots that tie your commitment to solely helping those who look like you, or speak like you. Dwelling means existing in an elastic relationship with causes with which one is in solidarity. Dwelling means that you are able to contribute to every activist space you step into because the freedom of others and their oppressions are your freedoms and your oppressions.

5. A Decolonial Manifesto Prioritises Non-English Languages to Challenge Dominant Ways of Knowing— One must never choose silence because of a supposed inadequacy in language. English is a language which runs off the tongue of the coloniser. Reading and engaging with other tongues and languages offers open gates for us to alternative imaginaries, ways of being, seeing and even thinking. This is fundamental to a project of decolonial liberation. Language does not need to be polished or articulated within the rules of grammar for the validity of a point to be valued and acknowledged. Some of the other languages which we speak outside of the academy are more real, close and intimate to us than English. By de-centering the English language we prioritise what is often portrayed as the ‘other’, bowing to the archive of a non-english mother tongue.

There is resistance in the act of acknowledging beauty and poetry in imperfection. It disrupts a singular conception of ‘perfect’ as the end goal of a teleological narrative used to justify domination, violence and colonial expansion. It prioritises an archive of another language and culture, questioning the dominance of a way of ‘knowing’ which is often taken as ‘the norm’ in most literary, academic and journalistic circles.

6. A Decolonial Manifesto Fights and Resists the Cooptation of Social Movements — Applying Audre Lorde’s maxim that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” we should always consider what the master’s house and the master’s tools are in a given situation, and how we might ultimately dismantle the master’s house via radical change, as opposed to merely renovating it by making minor adjustments to dominant systems.

7. A Decolonial Manifesto Respects the Enunciation of Anger as a Tool for Change — Anger chokes us when it sits un-enunciated in our throats. We no longer fear anger. To be angry is to let go of passivity. We have survived through our anger, and together we learn about its dimensions, roots and possibilities. If part of what we need to do in order to understand how world systems include and exclude our bodies, we must speak the truth. Our anger holds that truth. That which we see, that which we are subject to, and that which we feel moves our anger from a place of individuality to collective action.

Not fearing anger means that we are no longer afraid to oppose those who claim that we come from the past, and that there is no place for us in the ‘modern’ neoliberal world. Our anger unites us with our ancestors. The inequalities they were angry about are ones which we still experience. We do not fear anger. Our anger continues to unite us with our allies.

“It is better to speak remembering we were never meant to survive” —Audre Lorde.

8. A Decolonial Manifesto Reclaims Silence as a Form of Communion, Rather Than One Solely Based Around Grievance — A decolonial space is positioned to give voice to those who are silenced in the academy (and beyond). To do this we look beyond the conflation of silence with oppression (that is felt when one is in a space where one is voiceless), instead recognising the value and importance in being able to choose to be silent and still remain seen. An important aspect of this is to reestablish our relationship with silence and hesitation outside the parameters of previous experiences of feeling voiceless.

This not only speaks to moments of rest from the emotional and physical labour of a decolonial praxis and a wider sociopolitical system of productivity and efficiency, but values mental space for reflection and acknowledgement that we do not yet have the vocabulary to articulate. We value the human need to pause and be visible even when we are silent. In this sense, we value not performing and not producing as a form of radical praxis found in silence.

9. A Decolonial Manifesto Acknowledges That Togetherness Matters and Alleviates the Taxing Additional Labour and Solitude When Digging For Alternative Worlds — Being part of a community allows for the transformation of hostility into warmth, and also into grief. Such communities are ‘borderlands’, using Gloria Anzaldua’s words. When border thinking is about using alternative knowledge traditions and alternative languages of expression from outside what we have been trained to think of as the center, the additional labour of discovering less travelled pathways becomes less taxing as it no longer exists as an individual project (and should not be so).

A project of redefinition with a community of individuals who may not have met otherwise and whose questioning forms a complex web of intersections gives birth to co-learning pedagogies. Togetherness becomes an embodied value. Our learnings and knowledges slowly begin to complete one another. Beyond conversations from our respective disciplines, we accentuate the need for speaking and thinking from the border, unwearing the label of our previous academic training, and stepping away from argumentative attempts that could situate us as the gatekeepers of the academic disciplines we belong to. Doing so allows for a remembrance that such communities emerge as a marker of continuity, not rupture, and must exist in separation from the current discourses, since they may not have offered enough space for our thoughts, questions and silences.

10. A Decolonial Manifesto Chooses Decoloniality Over Disciplinarity to Build Stronger Solidarities that Can Converse Beyond Disciplinary Boundaries — A decolonial space looks to break down academic barriers and knowledge contained and atomised in different disciplines. We can begin this process by looking at how minds are disciplined through disciplines. In bringing together thinkers from different disciplinary backgrounds we can question and move beyond the impermeability of disciplinary boundaries, de-universalising knowledge by situating disciplines as relational to one another, and pointing to the significance of how knowledge is produced and reproduced in a certain ways through historical and social constructs.

In this sense, this perspective acknowledges ways of knowing not as ahistorical truths (framed in disciplinary categories) but rather as relational and specific ways of understanding the world, formed through historical relationship to capitalism and colonialism. By creating a space defined by decoloniality rather than disciplinarity, we contextualise how this compartmentalisation of knowing is formed through and perpetuates exploitative practices.

11. A Decolonial Manifesto Welcomes Radical Vulnerability For Collective Healing — Writing new narratives and breaking cycles of systemic oppression is an intergenerational and intragenerational process of collective healing, through which we heal our personal traumas by healing those before us, those after us and those with us now. We do so by allowing ourselves to be radically vulnerable with one another across time and space, sharing shame and pain, but also love and growth.

Radical vulnerability connects humans and instills in us the awareness that we are not alone in this journey of healing, and that from each other’s experiences we can draw strategies to navigate it. Most of us have been taught to hide our vulnerability, which is often described as a feminine weakness. Part of the decolonial project is precisely to deconstruct this patriarchal notion and recognize the massive amount of courage that vulnerability entails.

12. A Decolonial Manifesto Embodies Values that Hold Us. These Are Rooted In Generosity, Sharing and Compassion— As we softly hold each other’s hands in this journey of knowing and unknowing, the spaces which we make for ourselves are grounded in generosity, sharing, collaboration, kindness and compassion. We walk and breathe against the hegemony of individualism: in thought and being. We must be mindful of individualism’s role in colonial ideology, particularly in the positioning of individual vilification or punishment as a solution to problems that are systematic or collective in cause, even if personal in execution or presentation.

13. A Decolonial Manifesto Sees Healing From Embodied Silence As Fundamental: We Mend Them Through Dance to Open Up Possibilities of Rebirth — We must recognize the link between bodily expressions as decolonial practices. The body is an archive of our experiences, a store of memories - our own and those of our ancestors. Through bodily presence we participate, construct and call into question. Bodily presence is central to agency. Dance as one bodily expression happens through, within, and on the body. Dancing bodies display the struggles, vulnerability, and liberation resulting from cultural and political belief systems inscribed into them. Just as the fastening and silencing of the body is critical to coloniality, bodily awareness and liberation is crucial to decoloniality.

Dancing bodies may claim space – whether it happens in public, on a stage, or in one’s private rooms – and they display and contest external inscriptions. Through dance, we allow ourselves to feel what is within us, to control parts of our bodies that we may not even be aware of and liberate other body parts that we learned to tighten constantly. Through dance, we may break silence without words. Through dance, we - our bodies - may become ‘self’.

14. A Decolonial Manifesto Produces What Exists and What We Carry In Us. We Are the Knowledge We Seek—Through the lens of decoloniality, knowledge pertains to academia no more, and neither do the tools of its production. A decolonial prism recognizes knowledge as emerging from us. Any attempts at “knowledge production”, through research or writing, are merely transcriptions of what already exists, not a creation of what did not exist. Knowledge belongs to us and is within us.

Check out our suggested reading list!

This manifesto was curated and created by

Amina Alaoui Soulimani — Rabat, Morocco

Genevieve England — London, United Kingdom

It was co-written with

Alma Kaiser—Cologne, Germany

Fanidh Sanogo — Burkina Faso

Michelle Avenant — South Africa

Walid Hedidar — Tunis, Tunisia

Zakaria Bekkali — London, United Kingdom

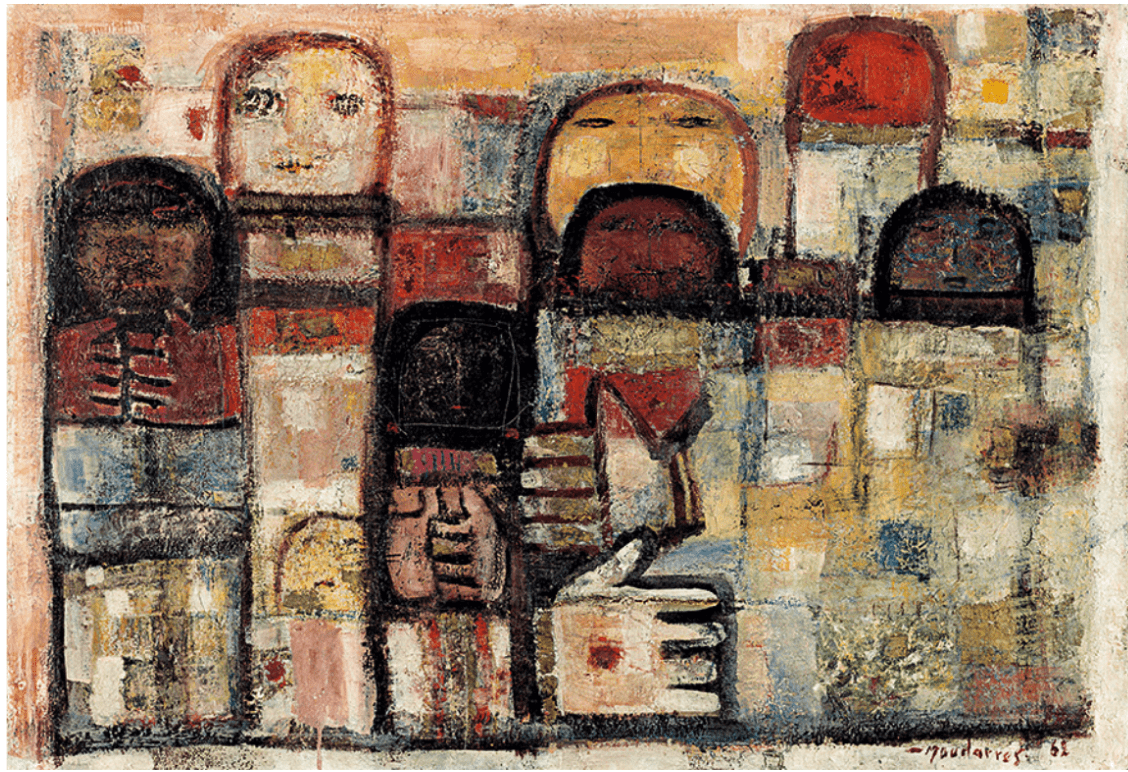

**Header photo credits: Fateh Al-Moudarres, Untitled, 1962. Included in ‘Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965’ 2016