“I know that in life there will be sickness, devastation, disappointments, heartaches, it's a given. What’s not a given is the way you choose to get through it all. If you look hard enough, you can always find the bright side.” -Rashida Jones

When I used to think about natural disasters, I would imagine places far away from home. Total devastation was something that happened in other countries, especially in the developing world. However, Hurricane Maria gave me a strong wake-up call. Our fragile power and water infrastructure collapsed, communications systems became practically non-existent, and the natural environment of the island was severely impacted. Even so, we held out hope. Hurricane Maria was a Category 5 storm that struck on September 20, completely devastating Puerto Rico as well as other islands in the Caribbean. In Puerto Rico, we had not experienced a disaster such as this since 1928, nor were we prepared for it. All the storms prior had caused minimal damage, and we had lulled ourselves into a false sense of security. Many even went as far as thinking we were invincible. As a child growing up in Puerto Rico, I remember listening to citizens claiming we were blessed or protected because none of the hurricanes that came our way ever made landfall. It was this kind of thinking that made it difficult to understand what was happening around me for weeks after Maria hit.

On Tuesday, September 19, our water, power and communications systems collapsed. Only one radio station remained on the air, trying frantically to keep everyone calm. As of September 23, three days after the hurricane, only 15% of a total of 1,600 cell phone towers on the island were functional. To remedy this situation, Google has been authorized by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to send out giant helium balloons above Puerto Rico in order to bring Internet connectivity back to the island. These measures were allowed because as of October 11, 83% of the cell phone towers in Puerto Rico were still non-operational.

The total collapse of communication caused an island-wide panic. Family members were desperately trying to find their loved ones and make sure they had survived the onslaught. As we drove out of Dorado on Friday, September 22, we saw crowds of people standing on the side of the highway, frantically trying to find cell phone signal. Police were forced to fine individuals to stop these citizens from risking their lives on the highway to make contact with the outside world. However, the Governor later prohibited them from doing so due to the extenuating circumstances. My family and I were able to contact our friends and kin on Friday because we drove to a different city which happened to have some signal.

The water situation was no better. After Maria, access to clean drinking water became scarce. This was due to the severe damage to both the water supply and treatment plants in Caguas and Arecibo. As of October 11, only 63% of residents had access to water. However, citizens' health was jeopardized because the water coming out of faucets appeared clean but was not deemed safe enough to consume in many regions. Due to a recent outbreak of leptospirosis on the island, (a disease often referred to as “rat fever”, since it is usually transmitted through contaminated rat urine), government officials recommend citizens boil their water before using it. However, since most Puerto Ricans still lack power, they are unable to boil water for consumption.

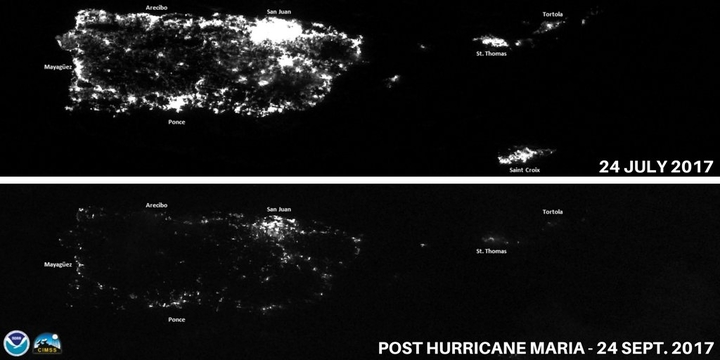

Puerto Rico’s power grid was deficient even before Hurricane Maria. Since the island slipped into a recession in 2006, most of Puerto Rico’s public utilities have fallen into disrepair. This was one of the main reasons that 95% of the island lacks power weeks after the hurricane and possibly for months to come.

Two weeks after the catastrophe, President Donald Trump visited the island. For many, the previous political turmoil we had experienced after his election seemed to disappear. After two gruelling weeks of seeing famine, destruction, loss and overall heartbreak, the visit of such an important official made many on the island hopeful. On October 4, 2017, he arrived at the island for the first time after the disaster and visited several areas of the major metropolitan region such as Guaynabo and San Juan. His itinerary included a press conference, a small tour of a suburb in Guaynabo, and finally a visit to a church in which he helped distribute some supplies to citizens. This route was highly criticized by citizens because the areas he visited had barely been affected by the storm. Many Puerto Ricans believed his trip could bring the help they desperately needed, yet most of what they received were insults. During his press conference, President Trump exclaimed that the Puerto Rican public had “really thrown the (US budget) out of whack.” He also claimed we should be proud that we had not experienced a “real” catastrophe like Hurricane Katrina while taking a moment to ask our governor how high our official death toll was at the time. President Trump then congratulated the public on such a low death count and proceeded with the rest of his scheduled day. At the church visit later that day, our beloved president deemed it necessary to throw supplies at the people gathered within, which led to the picture of him throwing paper towels that garnered global backlash. He managed to swiftly tear down any faith the Puerto Rican public may have had in the U.S. Government’s disaster response.

Weeks after the tragedy, there was a major disparity between the number of deaths that the government was providing and the ones the public reported. On October 5th, the Forensic Science Institute in Puerto Rico processed 200 death certificates after Hurricane Maria’s landfall, by which time the government was only reporting 34. They stated that the deaths had been related to patients that were interned at hospitals, but died due to a lack of energy to provide them with the care they needed. They also estimated the total amount of deaths to be close to 700.

The effect of the hurricane has been dire. Even now, as we near the end of November, Puerto Rico is still struggling to recover. In an effort to return the island to normalcy, most of the University of Puerto Rico’s campuses opened their doors on October 30th. After 40 days of being closed and with no power, water, or proper teaching conditions, the future seems grim for the students and faculty eager to start again. The student dormitories remain closed and the university has had to relocate students most in need. This is a temporary arrangement while they scramble to provide appropriate living conditions on campus. Classrooms are filled with fungi and contamination that make them unfit for use. I have talked to current students at the University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras, and they have assured me that while the campus is still “a mess” they are happy to be studying once more. “It was about time, we were going crazy. We missed it,” said Oziel Quiles, a current sophomore studying Biology.

My writing pales in comparison to the real tragedy most Puerto Ricans have lived and are still living through. The biggest emotional toll has fallen on the children of Puerto Rico. Professionals fear the consequences that this devastating storm will have on the children who had to live through it. In past disasters, like Hurricane Katrina, children who suffered in these catastrophes ended up needing significant psychological help. However, with the rate of destruction and loss, most families cannot afford health care, much less psychological treatment. With this grim future, many families are trying desperately to simply escape. A recent study by the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College suggested around 213,000 residents will leave the island over the next 12 months. The last time Puerto Rico suffered an exodus as large as this was before its economic turmoil in the early 2000's.

Two category five hurricanes making landfall in the Caribbean in the same year was previously unheard of, yet 2017 provided those assumptions wrong. Hurricane Maria was a terrifying reminder of our own mortality. It proved we were mistaken in believing we were invincible. Thanks to theefforts of a number of organizations, we are making our way to a slow, but sure, recovery. Something we should never forget is the rough lesson this atmospheric phenomenon has left us and seize the opportunity it has produced. As we rebuild, we have a chance to make a better Puerto Rico. It’s that vision that has many on the streets saying: “Puerto Rico se levanta” - “Puerto Rico rises again”. I personally favor Calle 13’s recent words during his Latin Grammy’s performance: “Puerto Rico no se levanta, porque siempre ha estado de pie” - “Puerto Rico does not rise again, because it never fell.”