The far-right has been on the relative fringe of European politics since the fall of the Nazis at the end of WWII, but political tides are beginning to turn against the centrist parties that have since dominated European governments. The perceived failure of Europe’s governing parties to handle the major migrant crisis has allowed far-right groups to benefit from growing popular dissent and see significant gains in recent national elections.

Several recent elections and ongoing campaigns suggest that immigration policy is a central concern for many Europeans, as increasing support for the far-right and its xenophobic and Islamophobic policies has increased in the aftermath of the European migrant crisis. Parties such as Germany’s far-right AfD (Alternative for Germany) received 13% of the vote in the most recent federal election back in September and became the third most represented party in the German Bundestag, the country’s legislative body. Germans’ discontent with their nation’s mainstream parties caused a drop-off in support which in turn lead to these parties losing more than 100 seats in the Bundestag. The situation in Germany is not an anomaly; similar trends can be seen across the European Union, such as Austria’s far-right Freedom Party receiving 25% of the vote in October or France’s populist right-wing Marine Le Pen finishing in second place in May’s runoff presidential vote.

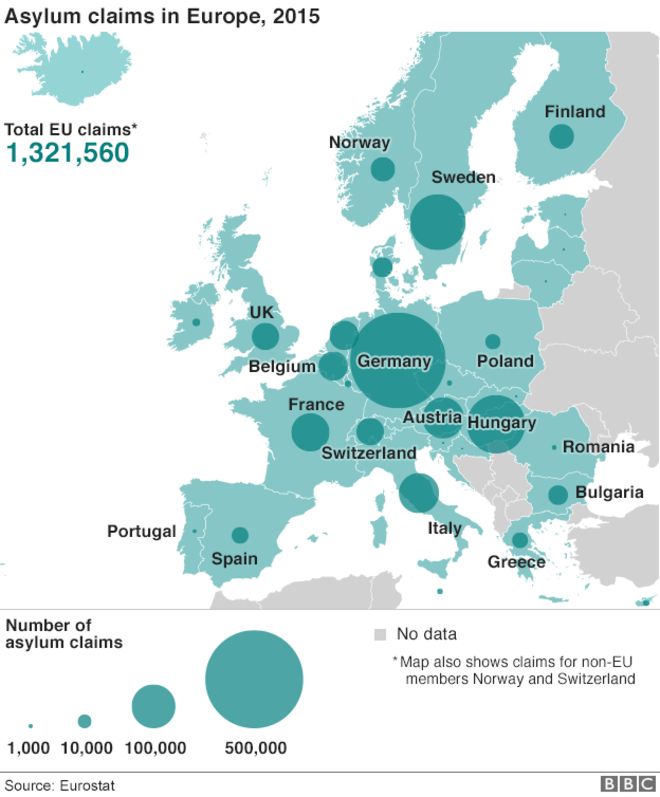

To comprehend this ideological shift, it is important to understand Europe’s migrant crisis. In 2015, over 1 million migrants flooded over the European Union’s borders. These people came mainly from the Middle East, but also from Eastern Europe and North Africa, with a majority coming from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq. These refugees were fleeing civil wars, violence, and abject poverty, searching for sanctuary within the EU. The Syrian Civil War and the rise of ISIS are the most prominent driving forces behind this mass migration, but crises in countries such as South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo are also forcing people to flee their homes and journey to Europe. Germany received the largest number of asylum seekers within the EU, with 476,000 asylum applications in 2015, but German officialsclaim that over 1 million people have entered the country in total. Austria and Sweden had some of the highest per capita asylum applications in the EU in 2015; only Hungary had a higher number of applications. A majority of Europeans believe the EU is “doing a poor job” of handling the crisis and a 55% majority supports a “Trump-style” Muslim travel ban. Although the number of people entering the EU has gone down since 2015, the effects of the crisis remain and European voters are not quick to forget.

Germany’s Chancellor Merkel’s change in views on this issue was one of the highest-profile examples of shifting public opinion on the handling of the crisis. Merkel originally fought for and defended her decision to allow massive numbers of migrants to enter Germany, but as public opinion began to sour, due largely in part to integration issues and rising crime rates within the migrant community, the Chancellor publicly recognized that the government’s handling of its open border policy was flawed. Stories coming out of Germany have stoked anti-migrant fears in many citizens of nearby countries. Recent polls show 65% of Austrians, originally welcoming of the influx of refugees, want an end to immigration from Muslim countries.This mismanagement created an opportunity for far-right parties to capitalize on growing xenophobic sentiments.

In Austria, center-right leader Sebastian Kurz recently won the chancellorship with a campaign defined by anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies. As foreign minister, Kurz took on immigration as a part of his political agenda, a duty not normally assigned to a government’s foreign minister. Discussion of immigration policy dominated the campaign season, with Kurz hammering his hard-line policies into the electorate. Kurz, 31, rebranded his People’s Party, changing its color from black to turquoise and using his own youthful image to paint his party as a new alternative for voters. He is currently in talks to form a coalition with the extreme far-right Freedom Party, which was founded by former Nazis. The last time the Freedom Party was a part of the majority government in Austria was in 2000. At the time, the EU placed sanctions on the country to convey its disapproval of its right-wing, extremist positions. However, sanctions like these are unlikely in the current political climate in Europe due to significant rightward shifts across the continent even though they were instrumental in formally rejecting extreme views in Europe.

The elections in Germany and Austria have emboldened far-right parties in other nations such as Sweden. The Scandinavian nation will not hold elections until 2018, but the far-right has already begun rallying supporters. The Nordic Resistance Movement, a neo-Nazi group, is seeing burgeoning support within Sweden. Lead by Paulina Forslund, the group spouts incredibly hateful rhetoric. For example, Forslund has referred to migrants as “imported scum” taking advantage of their country’s welfare systems. The Nordic Resistance Movement and other European fringe groups all employ similar rhetoric and strategies such as emphasizing white identity, culture, and heritage. They perceive the increasingly diverse landscape of Europe as a threat to their dominance and an attack on their cultural identities. By shrouding their xenophobia and hatred for non-white peoples in talks of preserving white heritage, they make their hateful ideology easier to swallow for skeptical European voters. In order to capture the votes of disgruntled and more moderate voters, these extremists turn to assailing mainstream parties. They attack failed governance and consistently criticize the “open border” policies that they claim to have undermined the status quo. These far-right leaders wish to convince undecided voters that their current leaders have ignored their concerns in favor of what they view as globalist and elitist policies.

These far-right movements struggle to capture pluralities and majorities of voters, effectively killing their chances of becoming core governing parties, but their growing popularity has pulled center-right politicians further from centrist positions that have dominated European politics for decades. Mainstream politicians are adopting far-right policies in an effort to reclaim the voters they have lost in recent years. Take the case of Sebastian Kurz’s center-right party, which ran and won on anti-immigrant policies borrowed from the far-right, or Angela Merkel, who in December of 2016 called for a ban on Muslim “full veil” coverings. This trend of increasing far-right support in response to growing levels of immigration is an interesting case in how certain issues can take hold of elections and shape policies for years to come. In the current age of increased migration and globalism, politicians must employ strategies to recoup disaffected and increasingly nationalistic voters while avoiding forfeiting their own values and abandoning the ideals for which they were initially elected.