There’s an extraordinary amount of information being directed at us right now, much of it uncertain, and an even greater amount of fear. It’s totally understandable if you’d rather not engage with yet another long personal reflection on our crisis, right now or at all! But what’s certain is that the way we approach collective concerns as a society will inevitably have to be reassessed, and I think it’s good that we’re already thinking about some of the changes we can make. In that spirit, I thought it might be helpful if I mentioned some feelings I’ve had on the unique ways in which LGBT+ people continue to be affected by - and interact with - the COVID-19 pandemic. I hope that, by having discussions about the intersections of oppression during times of crisis, we might apply ourselves more compassionately to similar intersections when time is with us again.

Something I’ve been thinking about is how the oppression of LGBT+ people and pandemics are both such deeply spatial phenomena. In South Africa and many other countries, lockdowns mean - for example - that many couples won’t legally be able to see each other for at least three weeks. Some people are considering these to be a new form of “long distance relationship.” Many people I’ve spoken to are planning ways of getting around the restrictions, by meeting in supermarkets or pharmacies or even at the doctor. Others simply feel understandably trapped and unable to seek comfort in troubling times, from the people they love most.

It’s been notable to me that the overwhelming majority of people I’ve seen making these considerations publicly are straight. I certainly don’t mean to diminish the stress of this situation - I also won’t be able to see my boyfriend, whom I love with all the light in the universe, and after being in separate countries for a few months it was disappointing news, to say the least. But the privilege of being straight and cisgender is that, for most (of course not all) of the couples I’ve spoken to, this is the first time they won’t be able to be in the same space as their partner, whenever and wherever they choose, for reasons completely outside of either of their control.

For LGBT+ couples, most of us already know what it’s like to live in long-distance relationships, even when we’re in the same city. We know the feeling of longing for the next time we’re able to shift an entire universe of logistics to be with each other for a few hours. We know every single way to see each other without our parents and families and friends and guardians and religious leaders and politicians and soldiers and judges and strangers finding out. We know how to lie to the police and the military when they catch us together in the streets or in our homes, and we also know (I also know) how to beg for mercy from them, while they scream at us and threaten us and assault us. We know what it’s like not to be able to be with the people we love in our homes, where we should feel safest. And we know how, even long after we’ve accepted ourselves and each other, and even when we’ve managed to find a way to see each other, and even when we probably won’t be caught, there’s still an unplaceable sense of unease when we meet, like we’re doing something wrong and we’re not sure what. I hope with all my heart that my wonderful friends are spared from this anxiety, if they find ways to be with each other during the lockdown, because it’s dreadful.

We’re also all experts in social distancing. I’ve read so many think pieces chastising people for being so careless with public displays of affection in the age of COVID-19, and they’ve all rung hollow to me, because that kind of recklessness was never a privilege I’d been allowed. LGBT+ couples know how to keep a metre between them so they don’t draw unwelcome attention. We know that we shouldn’t lean in too close to each other, we know that sometimes we shouldn’t sit next to each other, and we certainly know that we’re almost never safe holding hands or kissing in public. Please believe me when I stress that there isn’t a single city on Earth where at least one LGBT+ person hasn’t thought today about openly expressing affection for their partner and then decided against it. There is always a risk - homophobia and transphobia exists everywhere - but even where there is objectively little risk, almost all of us feel hyper-visible when we’re walking or sitting with our partners. We don’t want to be the next couple ostracised, turned away, abused, assaulted, arrested, raped, tortured or murdered because we thought we’d “probably be fine in this neighbourhood.”

This, of course, is only one aspect of the many ways we’re uniquely affected by COVID-19. LGBT+ people, especially older generations, carry the collective memory of the global antipathy towards the containment, treatment and prevention of HIV-AIDS, which continues to affect us disproportionately. We know that if you’re the wrong kind of people, like many other vulnerable groups, collective action will be decidedly less forthcoming. We know that, in clinics where nurses are being trained to deal with an impending coronavirus crisis, those same nurses frequently refuse to provide ARVs and other essential treatment to LGBT+ people, who will die as a result of being turned away. In some countries, healthcare professionals report LGBT+ patients to their families or to the police. In others, LGBT+ people elect not to seek medical attention, because the risk of dying from illness is outweighed by the threat of engaging with a violent system.

And then, of course, there’s the fact that LGBT+ people around the world are disproportionately poor, homeless, suicidal and vulnerable to abuse. For example, when university residences force their students to vacate within 72hrs because of COVID-19, LGBT+ students who are estranged from - or threatened by - their families, and are often without sufficient alternative support structures, are more likely not to have anywhere to turn to. Many faith-based homeless shelters - and thank God for them, truly - refuse to house LGBT+ people, especially trans* people. Government officials tasked with protecting vulnerable people in times of displacement frequently antagonise LGBT+ people. During a lockdown, domestic violence is guaranteed to increase. LGBT+ people suffering from such violence will often face ridicule, harassment, assault and detention when they attempt to seek assistance from the police.

Of course, everyone is affected by privilege and oppression uniquely and to varying degrees. But this doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist, and it certainly doesn’t mean that any straight and cisgender people are exempt from doing their part to consider the complexities of vulnerability during a pandemic.

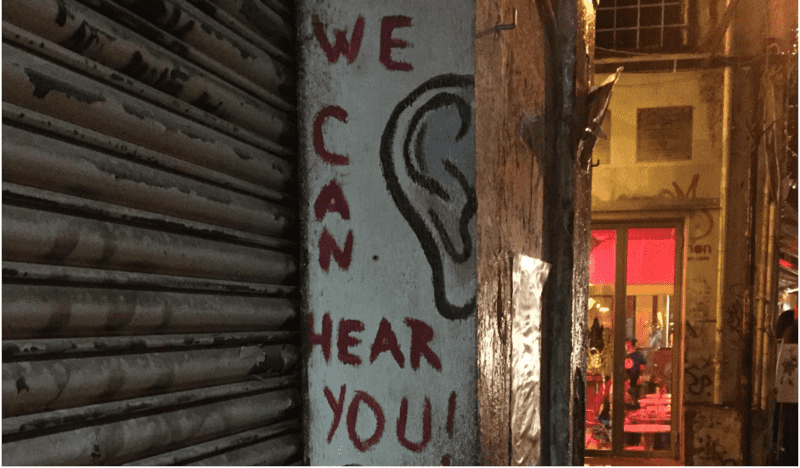

I would never want people not to voice their anxieties - after all, each of us is affected by this pandemic in ways with which everyone else is unable precisely to relate. But I ask, with all the love and respect and hope I have, that you use at least one of your moments of understandable anxiety to consider how other people aren’t protected in some of the ways you might personally be.

Here’s hoping for a future of radical tenderness ❤️