“I am not a Berber, I am an Amazigh.” This is what I, NOW, must say to different people in the West when I refer to Indigenous tribes in North Africa. I find the urge to do it because most people are not familiar with the term Amazigh, especially in the United States where I live. The word Berber is more known, which can refer to “people with a strange tongue.” When I say I am Amazigh in different western contexts, and explain where the people originate from, I often get corrected to “oh, you mean the Berbers.”

This uninvited, false correction is what Western knowledge does to us Indigenous peoples from the African continent. It silences our realities, our narratives, our identities, and our stories. It reduces us to “what the West calls us.” When we read some anthropological texts about non-Amazigh and Amazigh alike in the West, the knowledge becomes produced in Western contexts, it becomes valid, unquestioned, true. This very knowledge reduces the Amazigh to people with a peculiar accent. It masks their ethnic and cultural agency. Therefore, the term Berber essentializes Amazigh to these aliens, allowing for the self-determined Amazigh identity to be lost. This essentialization is not new, as an Amazigh woman from North Africa, I have been working to have my Amazigh identity recognized for a long time now, beginning since the time I lived in Morocco.

“I am not a Chliha, I am an Amazigh”“I am not a Chliha, I am an Amazigh.” This is what I could not say to a young woman about thirteen years ago in Morocco. I was visiting a young couple, who were friends of a friend, and were newly appointed physical education high school teachers in a small town in the south of Morocco. In that small town, Tamazight, the native language of the Amazigh, is more audibly visible. I italicize visible because the Tamazight language is not often heard in big cities in Morocco. One hears more Darija, The Arabic language variety spoken in Morocco. This couple considered themselves Casawi, belonging to the so-called “cosmopolitan” city of Casablanca where many young people strive to be Westerners or related to the west. Casablanca is a city of over three million people where you see different foreign companies, meaning that many young Moroccans must speak French, making it a compulsory language requirement to work in such companies. Casablanca is not a romantic movie about a couple that fell in love in an American café during the French colonization of Morocco. Rather, it is a city where many people strive to make a living in the largest and most expensive city in Morocco. Nevertheless, although Casablanca often represents a struggle, it also often presumes an air of superiority, a sense that those who live in Casablanca are somehow better than others in Morocco.

I remember vividly the time when I visited this couple about thirteen years ago in a small town South of the high Atlas mountains in Morocco called Tinghir. This young couple was very welcoming and eager to show me the beautiful scenery that this Indigenous town had to offer. However, I could not help but observe the way this couple referred to the Indigenous people of the town. They would utter comments such as: “dealing with the Chelouh is very difficult; they’re very stubborn people.” (Chelouh is the plural of Chelh.) The Arabic word “Chelh”, “Chelha” in the feminine, Chelouh in the plural, comes from the verb chalaha, شلح. One of the meanings of the word refers to the act of undressing oneself completely. In the passive voice, choulliha شُلِّح, means that a person was deprived of all that they own because of an encounter they had with muggers or robbers.

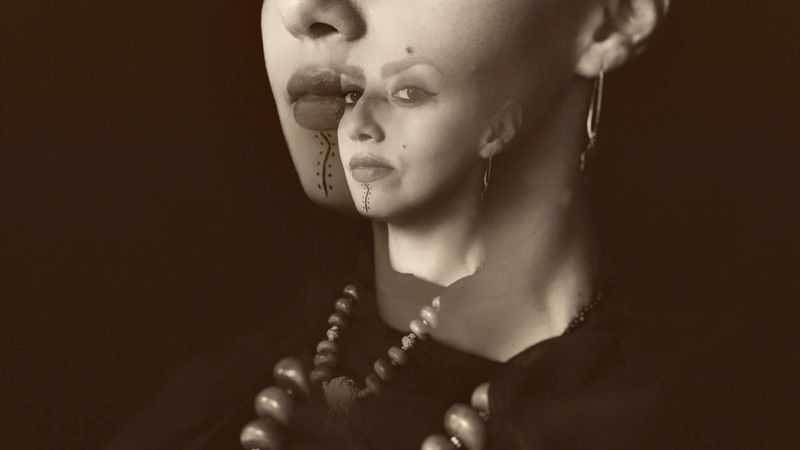

The couple were often laughing as they uttered the phrase “it is very difficult to work with Chelouh.” Chelouh “شلوح” in the plural form would be those who undress themselves. In this case, the Amazigh are portrayed as “lesser than,” “not having enough decency.” The laughter accompanying the utterance of the phrase made the couple somehow sound self-righteous and superior to the Indigenous town inhabitants. They created this distance between themselves and the town that was so unapologetically present. On one of the nights at the couple’s house as we were getting ready to go out for dinner, I wore my Indigenous jewelry that my mother had given me. The wife looks at it and says: “Mounia, Chliha” (Mounia, the little Amazigh girl). I did not know what to do with that comment. However, I remember that my feelings were anything but positive. The diminishing of the word Chelha to Chliha made it worse, as the structure of Chliha in Arabic refers to something smaller in quantity. Thus, Chliha, to me, carries with it this derogatory, rather than endearing, connotation of alienism.

I was the other, the Chelha. The phrase translated to me as, “the little country Amazigh girl,” or “the girl, who no matter what she does, she will always remain a Chelha.” That word she uttered bothered me for years. I couldn’t explain why until I decided to write about this experience. It bothered me because it did not sound complimentary; it sounded condescending. In my mind, I was thinking: this person is welcomed to live in this Indigenous town among the Amazigh, yet she is blurred by an illusioned superiority which she embodies through her language.

The term Chelouh (plural of Chelh), found its way to North Africa when Arabs came to settle in the region in the seventh and eighth centuries. The Amazigh were the ones whose lands, and languages, were conquered and undressed by the settlers. In other words, it is inconceivable for me to think that the word "Chelouh" is given to those whose land was conquered while others conquered them, undressed them from their identities. When the woman used that word, “Chliha,” I could not help but feel that word telling me: “Hello, imposter, naïve girl, country girl, the one who speaks a strange tongue.” These are the feelings the uttering of the word Chliha brought to me, but I could not articulate these feelings then. I knew that I was racialized based on my Indigenousness, but I stood there, speechless, very steadily, filled with conflicting feelings, yet somehow, I remained numb. As a guest in this couples’ house, I resorted to silence, but I felt alone when we went out for dinner. I was in a world opposite from their world. I was screaming, crying inside that my Amazigh people are considered strangers, imposters, Chelouh. How could a phrase create this big storm inside of me?

Language is powerful; when one word is uttered and more people start using it, more often, without questioning the impact it can have on other people, it gradually becomes normalized. Normal. I never spoke to that person again after my visit and she never inquired why. However, I wish I could have told her the reasons why our friendship could not grow. What I remember from that moment is that I felt miles and miles away from her. Whatever I could have said would not have mattered. My reality would not have been taken seriously. To her, I would still remain the Chliha country girl. No matter what I said. No matter in which language I said it. Something inside me prevented me from having that difficult conversation. I needed to protect myself. I took my distance. I do not regret it.

“Chliha” as a powerful racial slur is similar to the word “Berber”, in that it was also coined to refer to the Amazigh people. It was not coined by the Amazigh people themselves. The term was used by conquerors to refer to people who have a strange tongue. The othering of Indigenous people happened then, through the adoption of the term Berber, and keeps happening. What is even more frustrating is that this term is used in academia not only by non-Amazigh scholars, but also - sadly - by Amazigh scholars. The word Amazigh is not used enough in academic writing. The word that means the free people in our Indigenous language is not often recognized by library database search engines. The word Berber dominates the linguistic discourse.

I, the Amazigh, refuse to be named what I am not.In the past, I did not challenge the word “Berber” much because I was still trying to understand language colonization. Now, I refuse to be told, “I am Beber, ” and “I am too sensitive.” I refuse to be told, “it’s just what is historically known to people.” Many Indigenous people in the United States where I live are still fighting for social justice because of how they are perceived, racialized, and interpreted in texts and media. There is this lingering language of colonization and hegemony, and as an Indigenous Amazigh woman, I will continue to resist.

I will continue to resist this language colonization, this normalization of language slurs when referring to my people, or any Indigenous peoples. As someone who is a part of the academy, my tool is my pen. Just like the word “Chliha” was used to racialize me as an Amazigh female, the word Berber makes the Amazigh people distant beings identified by a distant past, a past told by others, a past where their history is not at the forefront of curricular books in the North African region.

Growing up in Morocco, I never read any stories by Amazigh authors. We read many stories by Arab authors. French authors. English and American authors. But never Amazigh authors. In history classes, we did not discuss in detail who the Amazigh are, their achievements, their stories, their identities. Instead, I would only hear about the Amazigh when there is an announcement of a festival in which the Amazigh are folkorized in their depiction. We were told in history classes that the “Berbers” were the first inhabitants of Morocco, and that’s the distant relationship I had with my Amazigh people growing up. Many Amazigh associations in Morocco and in the diaspora are working hard to reconstruct the narratives of the Amazigh. However, we need more presence.

As Amazigh in North Africa and in the diaspora, do we not have an ethical responsibility to reconstruct our narratives and those of our ancestors? Do we not have this responsibility to teach ourselves and our present and future generations what Amazigh embodies? Do we not have an obligation to educate those who are not of our tribes the rich history and depth that our peoples possess? This starts with decolonizing terms, redefining them to indigenize our narratives. It also highlights the importance of stories that do not make us the other, the foreigner, the Berber, the robber. The Chelh. Rather, this Indigenization of our narratives needs to mark our Amazigheity in its ancestral, ethnic, cultural, free, resilient, and intellectual narratives.